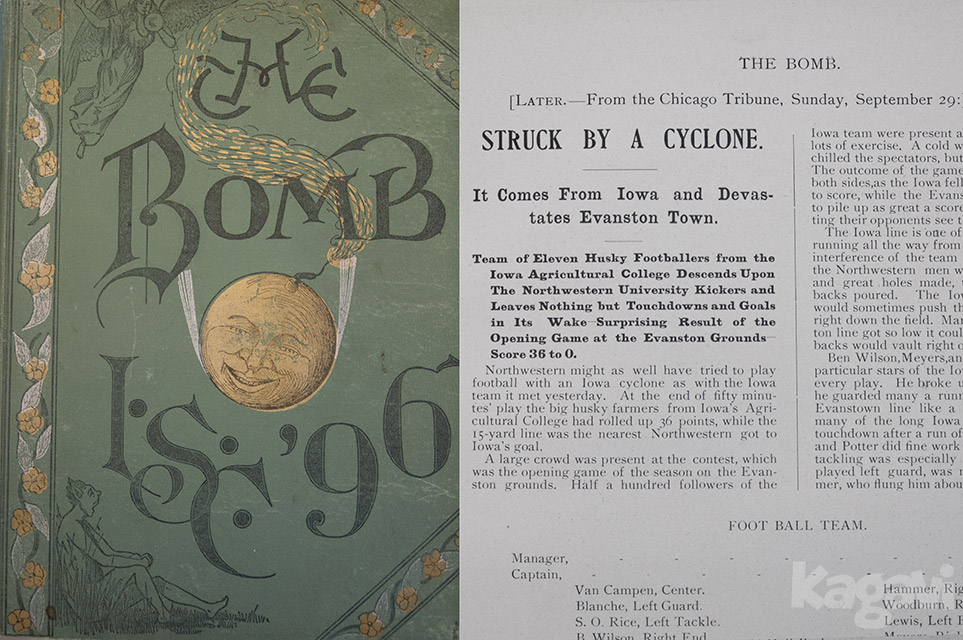

In 1858, Iowa State University was established as Iowa Agricultural College and the Cyclone nickname took root after a shellacking of Northwestern by the underdog Ames football team in 1895. Throughout the formative era of collegiate football, the Ames team experienced bed bugs, dubious referees, a train trip to Montana halted by snow and no food, and the agony of using hair as helmets. During this time, an unassuming black student named George Washington Carver helped the football teams as a trainer before eventually achieving worldwide fame with his scientific breakthroughs, inventions, and prodigious talents in the arts, which led Time magazine to dub him the “black Leonardo” in 1941.

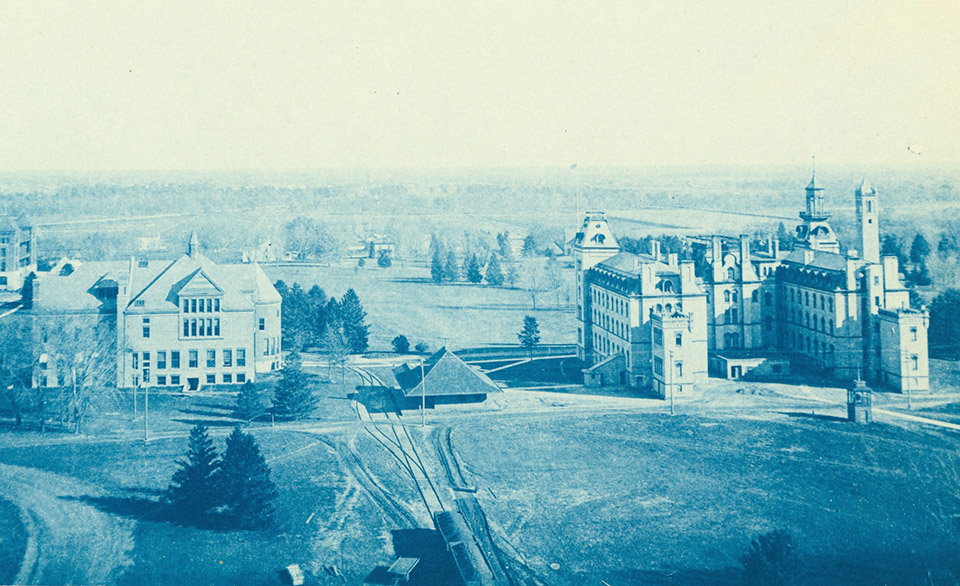

The first Ames football teams played on the grassy space in front of the imposing turrets of Old Main that dominated the IAC landscape. A newly forged bell behind Old Main was used to ring class into session and enforce curfew. Later the bell would be appropriated by the football team at Clyde Williams Stadium and it currently stands near Jack Trice Stadium as the Victory Bell. Two fires in 1900 and 1902 destroyed most of Old Main, leading to its replacement Beardshear Hall. (Interestingly enough, the University of Arkansas has a very similar building, also dubbed Old Main, still standing.) The Ames Historical Society put together an extensive history of Old Main with many large pictures of the campus at that time. In the second picture below, find the bell behind Old Main and the Dinkey tracks.

The ISU Digital Collections has many more highly recommended pictures of Old Main–including the fires–as well as some of the earliest football teams. In this photo of three members of the 1893 team, note the quilted pants and leather vest outfits.

A November 2013 sale by Legendary Auctions offered a very rare look at a leather uniform set from the 1890s similar to some of the Iowa State uniforms.

Burt German was a star back, team manager, captain, and coach of the early Cyclone teams. After several unsteady years, 1894 marked the first real season in Ames football history and German served as both the captain and the coach. German was embarrassingly introduced to football at the State University of Iowa in 1891 when he tackled the university president by accident. In a May 1955 article for the ISC alumni magazine, German wrote about his association with George Washington Carver:

“One evening on his way home from his other work, George came upon one of our players writhing in agony because of a badly strained muscle. The boy thought that his leg had been broken. In a typical act of kindness, George began gently to massage the leg and soon the boy was resting easily. The next morning his muscles were practically normal, and he came to football practice singing the praises of the kindly young colored man who had given him the ‘treatment.’ From that time on, George Carver was our rub-down expert.”

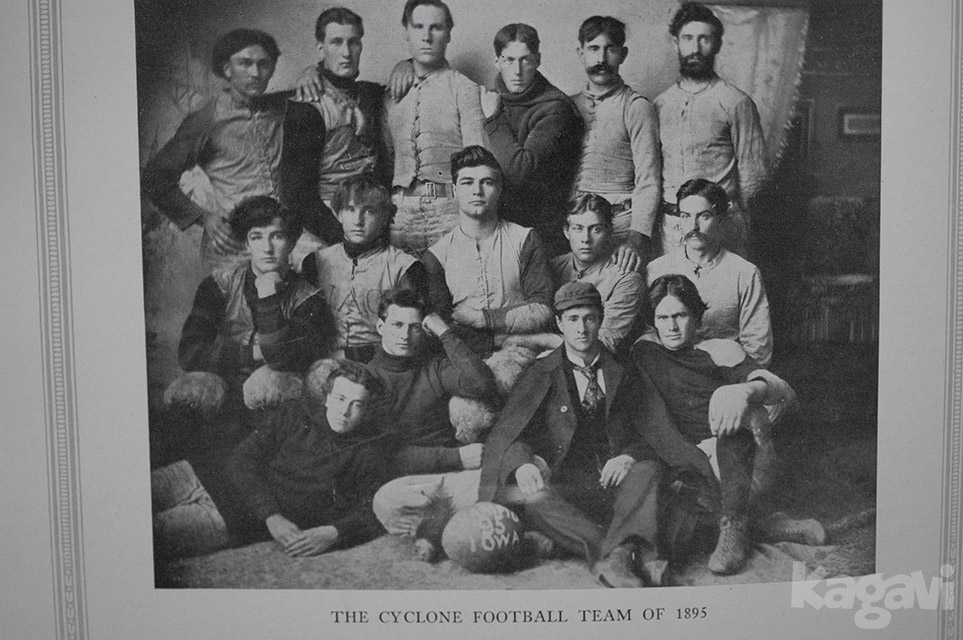

In 1895, German shared coaching duties with Hall of Fame coach Pop Warner who began the season for the Ames team before leaving to lead the University of Georgia team for the remainder of the season–an unorthodox arrangement that prevailed for several years. (Warner coached both ISC and Georgia in 1895 and 1896. In 1897 and 1898, Warner coached both ISC and Cornell. The last year with two schools was 1899–Warner worked for ISC and Carlisle Indian where he would eventually coach Jim Thorpe.) Strangely, German isn’t in the team picture of the 1895 team in the Bomb yearbook, but Warner is the burly fellow at the top left.

However, I stumbled across another picture of the team in the 1924 Bomb, which had a section on the 1895 team. I believe German is the person wearing the suit in the unlabeled picture–which would make sense since he was a player-coach that year. The wording on the football suggests this was taken after the season, which finished with a victory over Iowa.

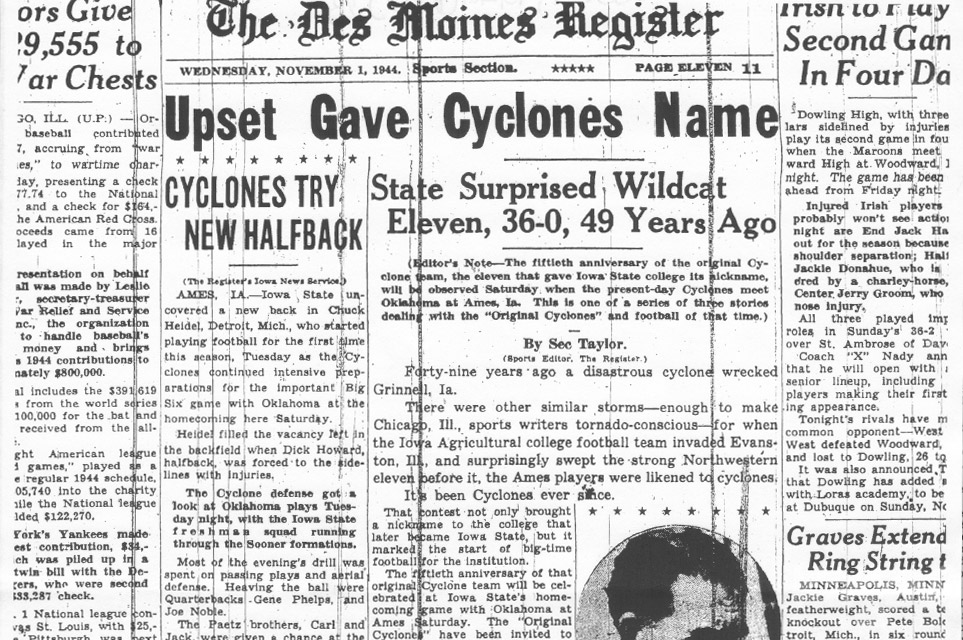

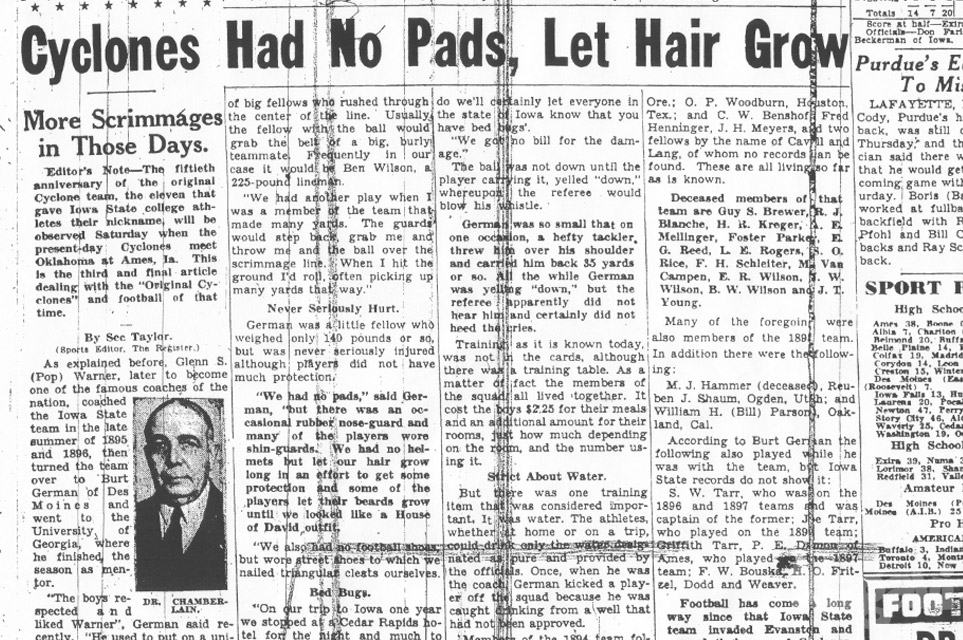

In 1944, the Des Moines Register interviewed members of the 1895 team for the 50th anniversary, which was observed during an early November 1944 game against Oklahoma. Legendary journalist Sec Taylor wrote the three part series full of fascinating stories, mainly supplied by German. The anniversary was celebrated one year early because “it is impossible to disassociate the squads of 1894, 1895, and 1896, since so many of the players held forth during the entire three seasons.” I will highlight a few items from each of the three parts.

“The first team to represent the Ames institution was organized in 1891. It played one game, defeating Nebraska, 22 to 0.” (The ISU football media guide formally recognizes the 1892 season as the first and Taylor confused ISU with Iowa who lists a 22 – 0 victory over Nebraska in 1891. After further research, the Nebraska student newspaper Hesperian confirmed this.)

“So in 1894 . . . it was necessary to solicit the faculty and the townspeople for funds . . . the usual charge for contests was 25 cents.” The only 1894 defeat came at the hands of “Grinnell one rainy Saturday afternoon. ‘Sheets of rain fell during the contest and the pools of water on the field were so deep that we had to unscramble ourselves quickly after each down to prevent drowning the fellows underneath,’ German said.”

“Pop Warner came to coach the team for the first time in the summer of 1895, but only to give it a start. When he left for Georgia, German again became the coach.”

In the game before the famous Northwestern game, our intrepid Ames team traveled to Butte, Montana by train to play the Silver Bowl Athletic Club in a 12 – 10 loss erroneously reported by Taylor as a victory. The train ride was “not bad at all for those days. The squad travelled in a combination tourist sleeper and diner and had its own chef. All went well until the train was snowbound and the chef ran completely out of victuals. By the time a foraging party was organized to visit the nearby town, all its groceries had been sold except cranberries, so the players had to subsist for the time being on boiled berries.”

“Pop Warner who coached the team . . . once told me that he had a difficult time convincing the Iowa State boys that Northwestern was just another ball club and that they could win from the Methodists.”

“Although the newly-named Cyclones defeated Iowa, 24 to 0, after that they lost to Minnesota 24 to 0, and to Wisconsin, 12 to 5. ‘I’m afraid some of us got a bit stuck up after that Northwestern game,’ admitted Burt German, who coached the team after Warner gave it a start, ‘and some of the boys didn’t train too well, either.'” (Taylor mixed up the dates of the games. Northwestern was on September 28, followed by Wisconsin on September 30. Minnesota was not until October 19 and Iowa concluded the season on October 28.)

In 1896, the Cyclone team played Missouri in Columbia. As German recalled, “when we took the field the Missouri captain announced that it was only a practice game and that we’d play only 20-minute halves. We insisted on 35-minute halves as provided by the rules. The Missouri captain said they’d be 20-minute halves or we’d not get the promised guarantee. That was serious since we’d had to take up a collection from Ames merchants and the faculty to make the trip. Our players walked off the field, angry all the way through, and went to their dressing room about a mile away. The crowd seemed to be equally displeased.” After an passionate plea by German, the crowd agitated for a full game and Missouri officials eventually caved. But German “had to work just as hard to get his angry players to dress and go back on the field. The Cyclones won, 12 to 0.”

“Games at Ames in those days were played on the campus on a field in front of where the main building now stands. There were no fences or bleachers. When the price of games was increased from 25 cents to half a dollar the fans rebelled and eventually the management was forced to admit girls free of charge as a compromise.”

In the entertaining conclusion, German shared several anecdotes. “The flying wedge was a popular and successful play. The ballcarrier would get behind a group of big fellows who rushed through the center of the line. Usually, the fellow with the ball would grab the belt of a big, burly teammate.”

“We had another play when I was a member of the team that made many yards. The guards would step back, grab me and throw me and the ball over the scrimmage line. When I hit the ground I’d roll, often picking up many yards that way.”

“German was a little fellow who weighed only 140 pounds or so . . . ‘We had no pads,’ said German, ‘but there was an occasional rubber nose-guard and many of the players wore shin-guards. We had no helmets but let our hair grow long in an effort to get some protection and some of the players let their beards grow until we looked like a House of David outfit. We also had no football shoes, but wore street shoes to which we nailed triangular cleats ourselves.'”

“On our trip to Iowa one year we stopped at a Cedar Rapids hotel for the night and much to our chagrin found our rooms already occupied. They were full of bed bugs. The boys began fighting them, grabbed chairs, or whatever they could find, and were so rough about it that they knocked most of the plastering off the walls. The manager insisted that we’d have to pay for the damages. ‘All right,’ I said, ‘but if we do we’ll certainly let everyone in the state of Iowa know that you have bed bugs.’ We got no bill for the damage.”

“The ball was not down until the player carrying it, yelled ‘down,’ whereupon the referee would blow his whistle. German was so small that on one occasion, a hefty tackler threw him over his shoulder and carried him back 35 yards or so. All the while German was yelling ‘down,’ but the referee apparently did not hear him and certainly did not heed the cries.”