Two names. One carved deep into the heart of Nazi Germany. One carved deep into the American Heartland …

The historical record is full of many connecting threads that help flesh out, somewhat tangentially, the forgotten life of Iowa State University icon Jack Trice. Small glimmers of his legacy are caught in the parallels of related stories such as the one that follows.

_____________

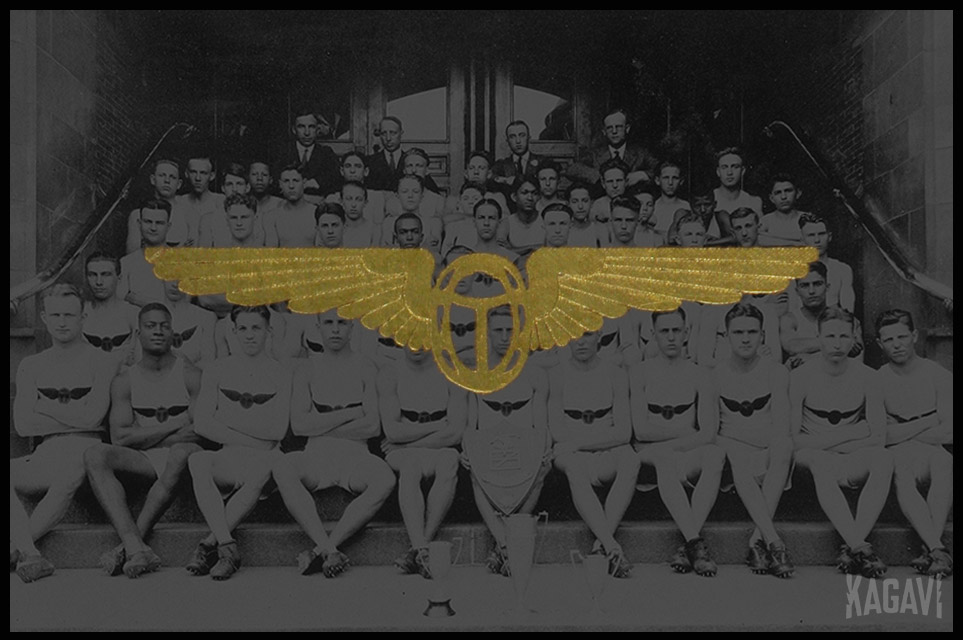

On a pleasant early September afternoon in 1930, nearly seventy prospective East Tech football players gathered at Woodland Hills Park–a popular spot about three miles south of the school–to await head football coach Johnny Behm and his staff for the first day of practice. Most players hitchhiked or caught rides with friends to the park, near where Jack Trice had lived with his relatives, but an unlucky few had to walk.

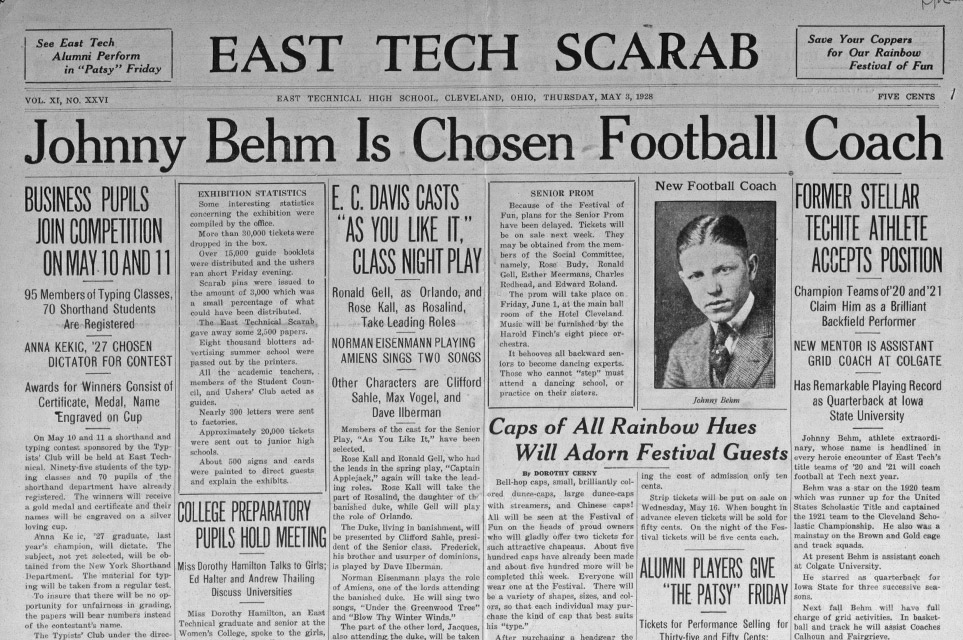

It was Behm’s third season at the helm of his alma mater after two years as an assistant coach at Colgate University in New York and a stellar career at Iowa State where he was an All-Conference quarterback. Many still remembered his undefeated prep career a decade earlier. Behm brought serious credibility to the job and was known for drilling players in the fundamentals.

In that first week of practice, Behm and his assistant coaches instructed a young sophomore with bright eyes and a slender frame named J.C., who was a solid athlete. While nothing special on the gridiron, this player was about to assume the fallen mantle of Jack Trice.

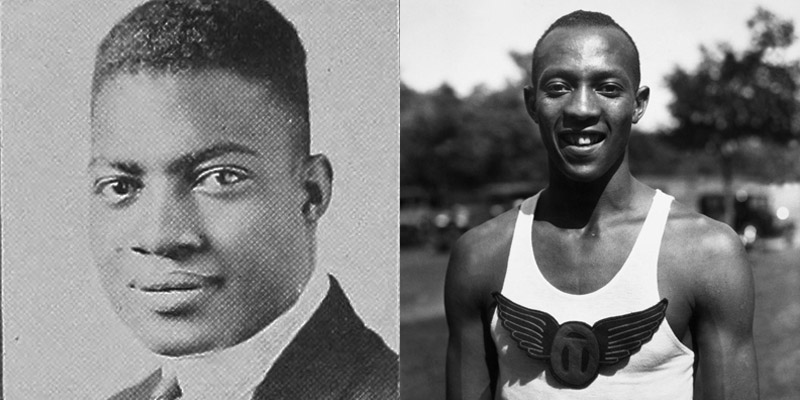

The sophomore player? Jesse Owens.

_____________

During the bloody throes of the Civil War, Jack’s father Green was born on a plantation in middle Tennessee, not too far from the Tennessee River. As a young man, Green joined the Buffalo Soldiers and spent some years in the American West before turning to farming in Ohio where Jack was born in 1902.

James Cleveland Owens was born in 1913 in a poor northern Alabama farming community, about ten miles south from the same river that Green drank from. Farming was a constant struggle for the Owens family and the spreading boll weevil epidemic exacerbated the widespread rural poverty of his early years. Sometime after World War I, the whole family moved to Cleveland, following his older sister Lillie who had found a job, husband, and better life.

When Jack’s mother Anna sent him to live with relatives in Cleveland after Green’s death, Jack was similarly thrust into the heart of a big, intimidating, belching city that felt a million miles away from the small town of Hiram, Ohio. It was just a few years later when the Owens family joined the Trice clan in the heart of Black East Cleveland. The esteemed author William Baker of Jesse Owens: An American Life was unable to pin down the exact date. “Estimates range from 1919 to 1924. Of the four different dates that Jesse gave for the event, the year 1922 appears most frequently in his reminiscences.”

The Owens family was swept up by the Great Migration tidal wave that saw millions of blacks move from the rural southern states into the arms of industrial northern states. WWI had severely curtailed the flow of European immigrants to the factories of the North, and after the war, further quotas created a labor vacuum that Black migrants filled. Baker wrote, “By 1920 just over 34,000 blacks represented 4.2 percent of Cleveland’s 800,000 inhabitants; by 1930 the total population increased only to 900,000 while the number of blacks more than doubled.”

While better than the south, Cleveland was hardly a paragon of racial peace. The Trice and Owens families were lumped together with thousands of other blacks, any misdeeds by one used as a referendum of the whole race. The Ku Klux Klan’s national popularity exploded and their inflammatory rhetoric was at a fever pitch. Emotions were thin and brittle. Nearby Luna Park, dazzling lights and clanging carnival rides achingly visible to Black children, maintained a strict segregationist policy that the Cleveland Gazette newspaper railed against.

Sports were one of the few ways that blacks could compete, but even that was often tenuous. As one of the stars of the East Tech machine, Jack cast an imposing shadow on young hopeful Black athletes. During his final year at East Tech in 1921 and 1922, he juggled school, football, track, and a steady job at nighttime. He may have encountered a youthful Jesse Owens playing kickball in the same streets. The East Tech players were heroes and local kids wanted to be them, to grow up and play in big games in the Cleveland Indians stadium up the road, to be featured in the newspapers. Like Jack.

_____________

When Coach Sam Willaman joined East Tech after playing professional football with the exalted Jim Thorpe, the school hadn’t really done much of anything yet, having only opened in 1905. As the coach of multiple sports, Willaman transformed the modest athletic program and with the 1920 football season, his efforts paid off in a big way. The Cleveland sports pages were full of reports on the powerful team slowly building at the school.

East Tech finished the regular season with an undefeated record, aided by Jack growing into his gangly body and a spot on the varsity squad as a junior, and the confident backfield play of Johnny Behm and his brother Norton, who both soaked up much of the attention and fame. The feat was repeated in 1921–all the more notable, since East Tech beat nearby power Scott High in Toledo both years.

To do so was no small thing.

Much like the current SEC streak of football dominance, during the 1910s and 1920s, whoever emerged victorious from the tough Ohio region was already one of the finest football teams in the nation, full of dominant athletes. Before WWI, teams from Ohio started winning national championships, first with Fostoria in 1912. The most notable team was Toledo’s Scott High Bulldogs, who won the state championship in 1916, 1918, 1919, 1922, and 1923, with most of those years ending in the national title game. (There was no champion named in 1917, presumably due to America entering WWI.) The only school to interrupt Scott’s reign was East Tech.

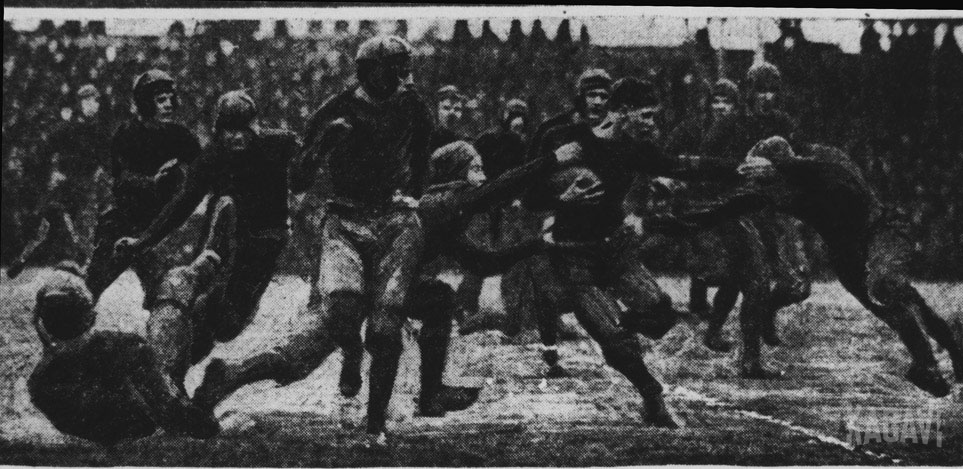

The year before East Tech temporarily ended their streak, Scott High concluded their 1919 season by traveling to the foggy coast of Washington to take on the incredibly powerful Everett High team, tying them in a bitterly contested clash billed as the mythical national championship game. After their undefeated season, East Tech repeated the same trip the following year, playing Everett on January 1, 1921. Willaman and his charges faced the same Everett team that had somehow become even more terrifying.

Already that season, Everett dispatched Utah’s finest team 67-0, clobbered Oregon’s best by a 90-7 score, and felled the famed Long Beach team 28-0. For good measure, they also beat a couple of college teams. The East Tech team lost in a close game 16-7, but the muddy field contributed to several critical fumbles and helped the heavier Everett team push around East Tech. Some of their players were in their twenties.

A long period of research into this game has revealed a lone printed photo of the game. The halftone print has been altered with white markings for better reproduction, but we can see Behm slithering his way through the mud with the ball, wearing no helmet. Behind him Jack is charging, helmet pulled low and long arms cutting through the chill, fallen opponent in front of him. (This is perhaps the definite photo of Jack in high school game action and joins our original Iowa State photo discovery from 2014.)

Jack’s performance was lauded as one of the few highlights for East Tech, while Behm dazzled as well. They were on the same level as Everett, just younger and lighter. All the more notable, considering Everett was led by halfback George Wilson, who ended up in the College Football Hall of Fame. Many players from Everett, along with their coach Enoch Bagshaw, attended the University of Washington the following year and eventually went to two Rose Bowls. Attempts to stage another postseason game in Jack’s senior year of 1921 fell through and the East Tech team finished that year as undefeated state champions again.

Their success carried onto the track team, also coached by Willaman, with Jack and Behm helping the track team to two consecutive titles in 1921 and 1922, the first for the school. This feat would not be replicated until Owens came along. These were hard-earned titles. Cleveland was no sparsely populated tumbleweed town.

When the calendar turned to 1923, Jack was at Iowa State dreaming of big things while Owens roamed Jack’s old stomping grounds. Across the Atlantic Ocean, a dark storm was fulminating in Munich, Bavaria. The doomed Beer Hall Putsch coup in November 1923 landed a young Austrian named Adolf Hitler in prison where he wrote his incendiary Mein Kampf memoir.

The stage was set for Jesse Owens.

_____________

Football in Ohio has always been practiced with religious fervor and East Tech was known as a solid city power that had briefly ascended to the top of the Ohio prep football world in 1920 and 1921. The Roaring Twenties were now in full swing and the school was eager to enjoy success again. During these heady times of unbridled optimism, anything seemed possible. Willaman was the coach at Ohio State and his name in the local papers continually reminded East Tech of those glory days.

The answer was clear. Behm, the captain of those teams, was offered the job in 1928.

During his playing career, Behm’s small, slippery stature caused fits for opponents and, on occasion, even Johnny himself. In a memorable incident shortly after returning to East Tech in fall 1928, he was punished by a teacher for not running an errand fast enough. The only problem? The teacher thought he was a delinquent student and not the new football coach. He blended in easily.

Jack’s memorial photo was still on display at East Tech and the spirit of those teams still echoed through the hallways. At East Tech and Iowa State, Behm was perhaps the closest teammate to Jack and often sat with him on long road trips. Would East Tech see another athlete like Jack ever again? Behm was eager to try, and would also help coach multiple sports including track.

It didn’t take long for the economy to crater and the Great Depression followed Owens to East Tech when he enrolled in September 1930. Much like Jack, Owens found the school a largely white one. Baker wrote, “Black students at the time numbered less than 5 percent of the student body, a figure that would rise dramatically in the following decade as blacks sought to equip themselves for skilled trades.” Thanks to his upbringing in rural Alabama, Owens read poorly and struggled to keep up in his academic classes. A trade school wasn’t the place for a poor Black kid to learn how to study. Sports were his salvation.

Returning to the first week of football practice in 1930, when Owens took his stab at becoming the latest East Tech star under Behm’s watchful eye, it soon became clear. Wearing his usual practice attire of baseball pants and sweatshirt, Behm turned his attention elsewhere. Owens was not the answer. When he tried out for basketball, the same happened. Baker wrote, “In neither sport did he last for more than a week or so. An ankle injury in basketball prompted his principal to urge him to put all his ambitions into track, and Jesse complied.”

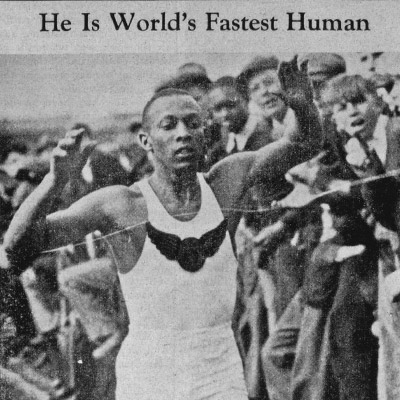

The new East Tech track coach was Edgar Weil and he was totally green, having never even competed in track, let alone coached it. Along with the other East Tech coaches, Weil asked Owens’ junior high mentor Charles Riley to help coach, which he happily accepted. Behm and the other coaches watched with interest as Owens started to pile up accolades. After wisely focusing on track, Owens led East Tech to two consecutive state championships in track, (tying Jack and Behm’s feat) and capped his prep career in early summer 1933 by setting a new world record in the 220-yard dash and tying the 100-yard dash record.

In college at Ohio State, Owens took place in arguably the most famous track meet in history, the 1935 Big Ten Championships in Ann Arbor, Michigan. While nursing a back injury, Owens won the 110-yard, 220-yard, long jump and 220-yard hurdles in the span of just 45 minutes. The long jump was won with just one single attempt.

That’s not all. In every single event, Owens set a world record.

He was ready for Germany.

_____________

Hitler rode the popularity of Mein Kampf into a stranglehold on the Nazi party and his ideals came to a head in Berlin as the world wobbled towards a conflict for the ages. Hitler was using the Olympic Games as a political statement and demanded the world’s attention and respect. Red streaks of Nazi iconography were sickeningly draped everywhere. German troops stood at eager attention. Undesirables were banned. The Games would be perfect and a coronation. Hilter’s personal photographer recorded some scenes in color through the 1930s and they still appall, decades later. (See the archive here.)

Stepping upon the cinder track, Owens was continuing the struggle started by Jack and so many others before him. Fighting for anyone who was ever discriminated against. The undesirables. The Jews. The blacks. The handicapped. Using the undeniable clarity of athletics as a tiny wedge into changing society.

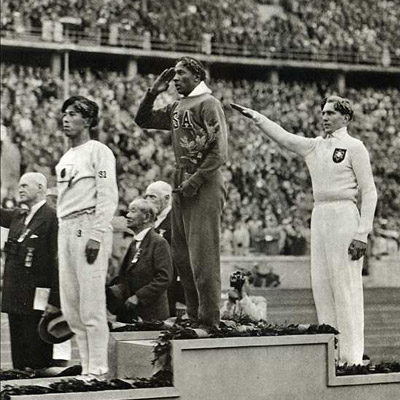

Under the watchful eye of the swastika, Owens won four gold medals. Many volumes have been written about these feats and they were recently memorialized in the film Race. With each victory, the stonemason chiseled his name in a colossal slab of gray stone along other gold medal winners of the Games, each new line straining against Aryan superiority, where they still stand today:

100m LAUF OWENS U.S.A.

200m LAUF OWENS U.S.A.

WEITSPRUNG OWENS U.S.A.

4 x 100m STAFFELLAUF U.S.A.

One particular photo has always stuck with me as a metaphor for the charged times. Here’s Owens, celebrating his gold medal, hemmed in by future enemies Japan and Germany, the Nazi salute pointed right at his head. The purity of victory standing tall in the enemy’s cauldron. Three years later, Nazi Germany invaded Poland.

Incredibly, in addition to Owens’ four golds, there were three more East Tech athletes representing Team USA in Berlin and they all won medals. David Albritton, who was Owens’ East Tech and Ohio State teammate, won the silver medal in the high jump (after setting the world record earlier that summer). Lou Laurie and Jackie Wilson were still students at East Tech when they entered the boxing competition and Wilson emerged with a silver (bantamweight), Laurie with bronze (flyweight) and the Val Barker Trophy, given to the most stylish boxer. First awarded in 1936, the Val Barker Trophy has gone to a gold medal winner fifteen of eighteen times. It took a rare boxer to be recognized sans gold.

Cumulatively, four gold medals, two silvers, and a bronze were won by East Tech. If East Tech was a country, they would’ve finished in tenth place out of forty-nine countries in the gold medal standings, as well as fifteenth in the total medal standings. When Owens returned to America, his impressive victories unfortunately hadn’t made much of a dent in America’s racial attitudes.

World War II ended up canceling the next two Olympic Games. Ironically, following Berlin, the 1940 Summer Games were to be held in Tokyo. Both nations, chief aggressors of the war, certainly laid waste to the goal of the Olympic Movement “to contribute to building a peaceful and better world.” Although Owens’ career was over, East Tech was not done on the world stage. In the austere backdrop of post-WWII London, the 1948 Olympic Games saw yet another East Tech track star burst into America’s consciousness.

_____________

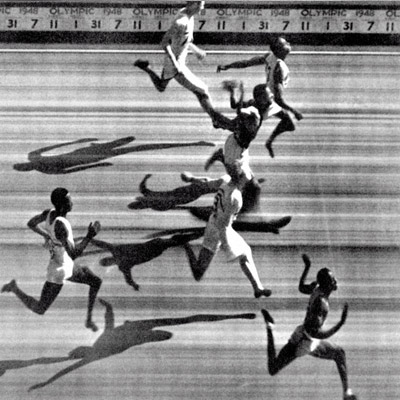

Harrison Dillard was born in Cleveland mere months before Jack’s death and became inspired to pursue track after witnessing Owens’ ticker tape parade in Cleveland after the Olympics. After serving in WWII, Dillard became one of the world’s best hurdlers. In the lead-up to the London Games, he shockingly failed to qualify for the American team in the 110m hurdles (despite having won over 80 consecutive races) and barely qualified in the 100m. Unperturbed, Dillard won the 100m in a memorable dead heat over fellow American Barney Ewell. The race was so close, judges relied on photo-finish technology–typically used for horse races–marking this race as the very first photo finish in Olympic history. (See the race here.) Note the finish line is not straight, but rather angled to the left. Dillard is on the bottom.

Dillard won another gold in the 4 x 100m relay and four years later, he finally got his 110m hurdles gold medal in the 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki, Finland, along with a repeat gold in the 4 x 100m relay.

The two East Tech Olympians that bookended the WWII years were a perfect illustration of the elite level of competition in Cleveland. Descriptions of Jack as one of the finest athletes to ever compete for East Tech still ring true. We are left to wonder what heights Jack could have achieved along the level of these other men. After all, Jack held the school record in the shot put, which remains a classical expression of explosive strength. Could he have transitioned to the Olympics? We will never know. What about football?

The year after Behm graduated from Iowa State, the 1926 All-American team had Michigan quarterback Benny Friedman as a consensus selection. Friedman was a teammate of Jack and Behm at East Tech, but just couldn’t break through the talented lineup and ended up transferring to nearby Glenville High. One Michigan and New York Giants career later, Friedman was elected to the College and NFL Hall of Fame. That’s how good East Tech was. Even the scrubs went on to Hall of Fame careers.

Behm remembered Jack’s talent in a 1979 interview, remarking “(Jack) had speed, strength, and smartness. There is no question in my mind he would have become an All-American.” Cyclone teammates weren’t the only ones to feel this way. Some years after Jack’s death, a prominent observer of college football placed him firmly in the same pantheon as a select group of other Black players in the sport’s first fifty years who were later elected to both the NFL and College Football Hall of Fame. This on the basis of barely over one college game completed. One. That’s how far Jack’s fame spread, despite the virulent racism of the times that tried to discredit any achievements by blacks.

What about Jack’s social impact? His famous letter revealed an intelligent man, yearning to make a difference. Perhaps he could have followed in the pioneering footsteps of Paul Robeson, the All-American player at Rutgers in 1917 and 1918, who went on to international fame as a NFL player, singer, actor, and Civil Rights figure. Maybe Jack’s interest in agriculture would have led him to George Washington Carver, the former ISU football trainer, student, and teacher.

When the Greater Cleveland Sports Hall of Fame inducted its inaugural class in 1976, Jesse Owens and Jack Trice joined Johnny Behm in the pantheon. Harrison Dillard and David Albritton were also elected that same year. To date, both Jack and Behm are the only two to be honored from the dominant 1920s East Tech football teams.

Finally, Jack’s coach in high school and college, a somber man nicknamed “Sad Sam,” left no doubt about his legacy. Willaman played with Jim Thorpe, perhaps the finest athlete of the last 100 years, during the peak of his career on the Canton Bulldogs football team. Willaman wasn’t prone to exaggeration, but in 1924, he wrote after Jack’s death:

“In another year he would have been the greatest football star in America–a super-man.”

Even after time has rubbed away all other names, they remain.

_____________

Two stadia. Two names etched permanently into stone. One triumphant, one tragically cut short. Both remembered as heroes.