Jack Trice teammate Ira Young’s estate

Earlier this year, I shared two significant pieces from Jack Trice’s life: the first photo of Jack in game action and an important football jersey from the infamous 1923 Minnesota game. Both of these finds came from the estate collection of Iowa State football captain Richard Ira “Pep” Young, who graduated from ISU in 1924 with a degree in civil engineering.

Ira Young was the ideal homegrown Cyclone student-athlete who played three sports during his time in Ames. He graduated from high school in the small town of Jefferson, Iowa, directly west of Ames on Highway 30. When Ira entered Iowa State College in fall 1920, he became a pledge of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon (SAE) fraternity and these bonds endured for the rest of his life. As a junior in 1922, which was Coach Sam Willaman’s first year at Iowa State, Ira’s fine football season led the team to vote him as the captain-elect for the 1923 season. Ira capped his Iowa State career with multiple letters in football, basketball, and tennis.

I have been fortunate enough to acquire Ira’s entire estate and can’t wait to share it with all of you. Here’s a look at some other key pieces.

Jack Trice’s lost jersey

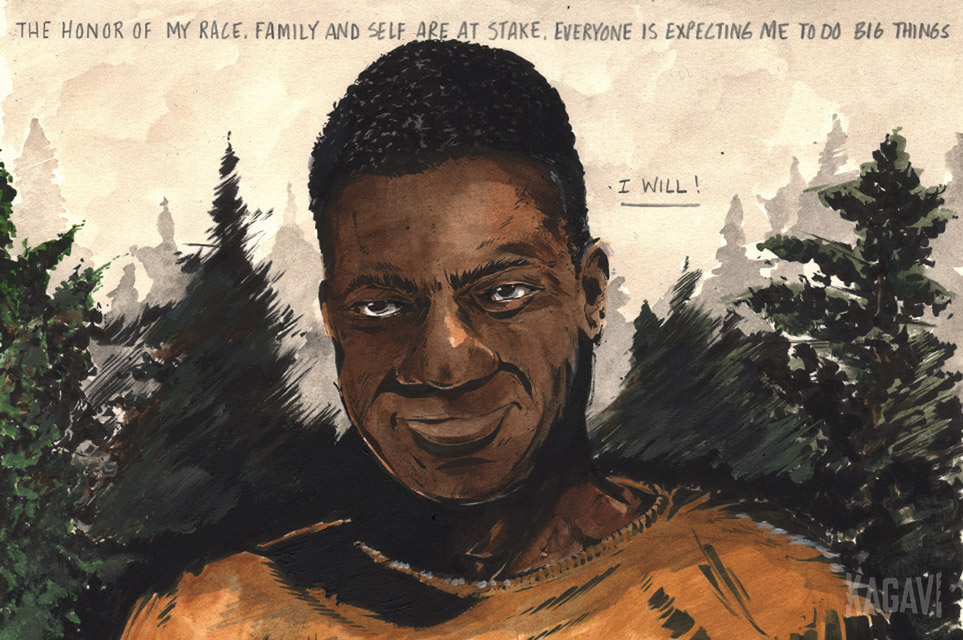

When Jack Trice died of fatal injuries suffered in his first major game as Iowa State University’s first Black football player in 1923, he left behind a letter written to himself on the eve of the game. The full letter, which was discovered before his funeral, has become an iconic symbol of determined hope and effort triumphing over ugly discrimination. Today, Jack’s famous words sit in a thick vault at Iowa State as the beating heart of an entire campus.

The other prominent symbol of Jack’s brief life remains his distinctive football uniform with five vertical strips. When Jack walked onto the Minnesota field wearing his gold jersey, he was the only Black man on the field surrounded by a crowd of over 20,000 Minnesota fans waving colorful pennants and chanting. At that moment, the words of his letter were surely reverberating through his heart to do big things. When Iowa State finally created throwback uniforms in 2013 to honor his story, they used pictures of his jersey as reference. No trace of what happened to Jack’s jersey has ever been found and it was probably thrown out at some point, but what if it wasn’t?

We set out to find Jack Trice’s lost jersey.

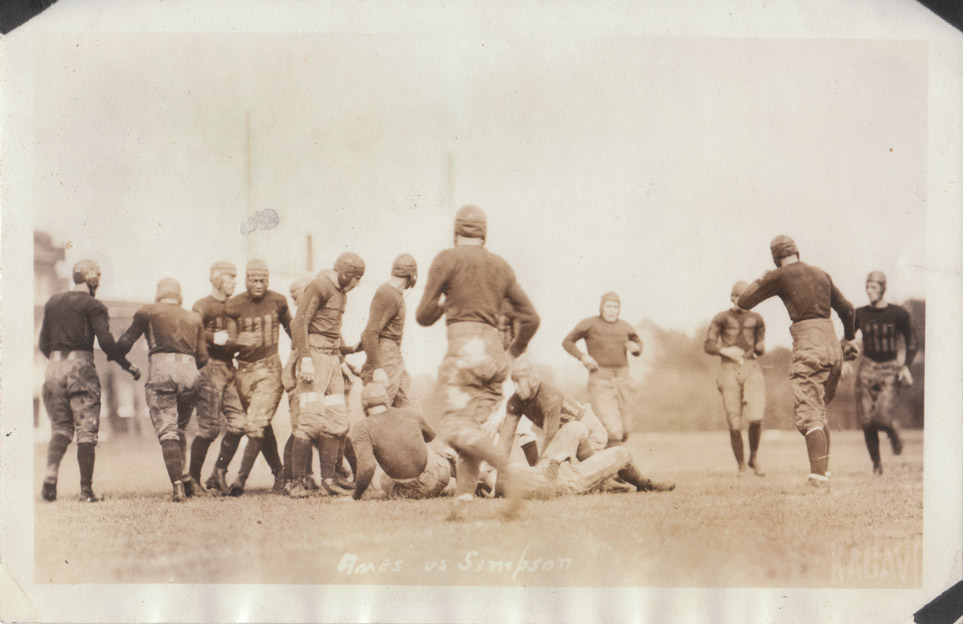

Original Jack Trice game photo found

To kick off the upcoming football season, I am pleased to share a significant acquisition in my ongoing Jack Trice research. For the first time ever, I am proud to present the only original picture of Iowa State legend Jack Trice in a football game. This is a new image of the Ames vs. Simpson game nearly 91 years ago, which was the first varsity game for Jack. The picture has never been seen in public before.

Jack Trice: fraternity brother

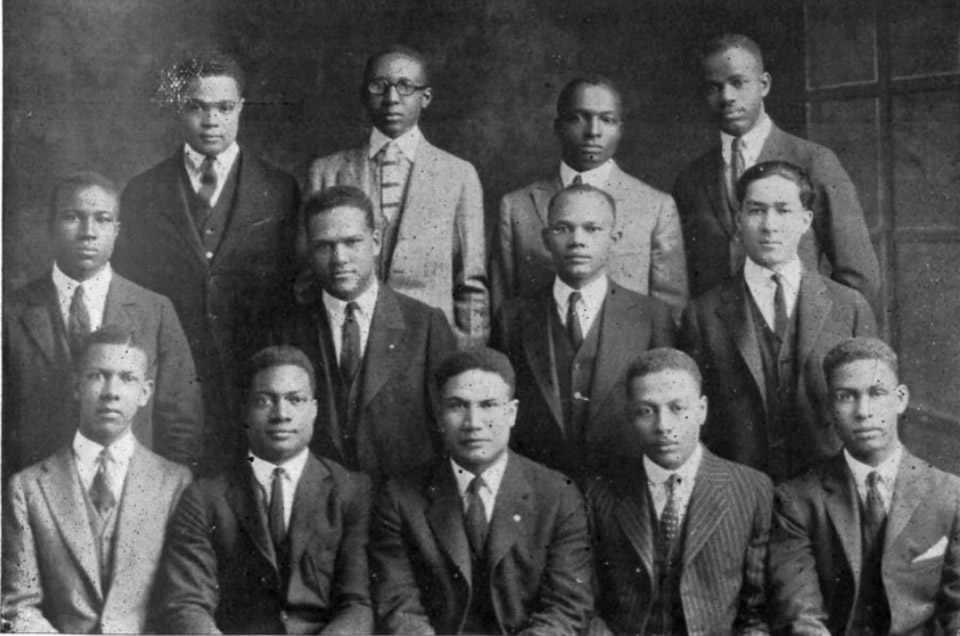

While researching Iowa State legend Jack Trice’s life recently, it dawned upon me that none of the published articles or books mentioned his close ties to the new Alpha Phi Alpha black fraternity formed in Des Moines under the Alpha Nu chapter. When Trice’s widow Cora Mae recounted the day of his death, she mentioned his fraternal brother Harold Tutt, who accompanied Cora Mae, and Jack’s relatives back to Cleveland via train with his casket after the funeral on Iowa State’s central campus.

After quite a period of time scouring historical records and archives, I was pleased to find some new information on his life. For example, it was mentioned that Trice became certified as part of Iowa State’s life saving corps. However, the real thrill was finding a new picture of Trice, as there are a tiny handful of pictures still in existence.

For the first time, I am proud to share an incredibly rare picture of Jack Trice and Harold Tutt sitting proudly for the very first picture of the newly formed Alpha Nu chapter. Meetings took place in Des Moines near the site of the airport and the chapter was a joint collaboration between Iowa State and Drake University. (Tutt can be seen in the top left corner.)

This is yet another aspect of his life that has gone completely unexplored and we hope to bring more new insight to this part of his story. Stay tuned to Kagavi for more groundbreaking research into Jack Trice’s life.

From Madison Square Garden to the Big 8 and back

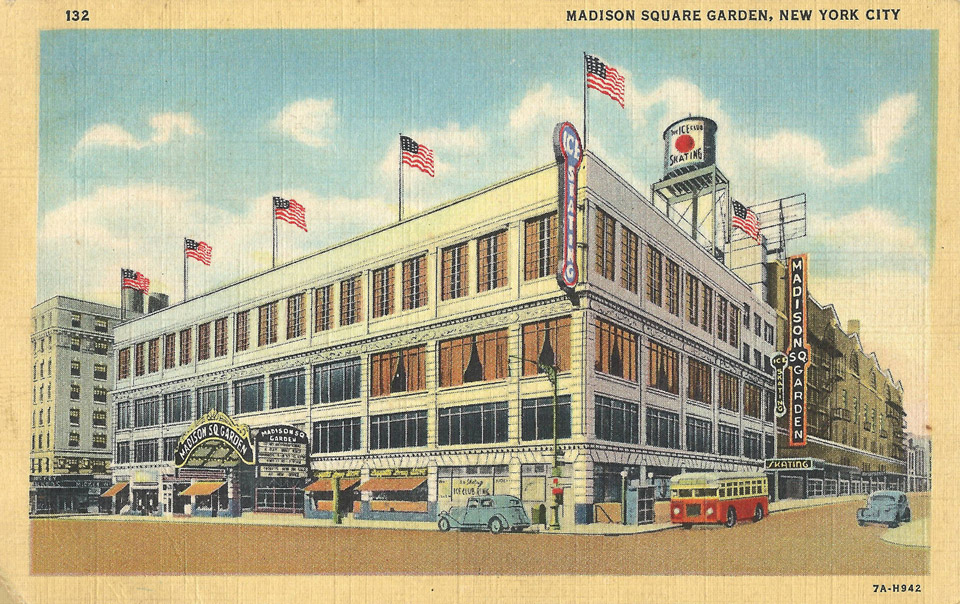

As Iowa State University invades New York City for the NCAA tournament this weekend, I wanted to take the time to explore the tale of Coach Fred Hoiberg’s maternal grandfather Gerard L. “Jerry” Bush, who starred for St. John’s University in the 1930s and had basketball games at Madison Square Garden before playing a pivotal role in the early professional leagues that birthed the NBA. After his athletic career was over, Bush coached at the University of Toledo and the University of Nebraska, and was named to the Hall of Fame at both schools. Along the way, I was struck by the many similarities between Jerry Bush and Johnny Orr. The story of Jerry Bush has played a major part in Fred Hoiberg’s life and the story starts at Madison Square Garden nearly 80 years ago.

The first Madison Square Garden was originally constructed as a train depot before P. T. Barnum converted it into a Hippodrome. In 1879, the roof-less arena was renamed Madison Square Garden and stood for just over a decade. The new Garden, built in 1890, was a Beaux-Arts masterpiece but struggled to turn a profit prompting the New York Life Insurance Company–who held the mortgage–to tear it down for their iconic headquarters building in 1925.

The third Garden, built away from Madison Square for the first time, eschewed grandiose architecture for a simplistic box that focused on the events within. Over the subsequent four decades of existence, from 1925 to 1968, the Garden saw many iconic boxing matches and welcomed both the New York Rangers hockey team and the New York Knicks basketball team as tenants. The Garden’s impact wasn’t limited to just sporting events. Political rallies were often held there and in 1962, Marilyn Monroe sang her famous song “Happy Birthday, Mr. President” to John Kennedy less than three months before her death. It was this very Garden where Jerry Bush would have his first taste of athletic fame.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Bush started college in 1934 at nearby St. John’s University, which was also located in Brooklyn at the time. The basketball team formed in 1908 and the first coach to enjoy sustained success was Coach James Freeman starting with the 1927-28 season. His “Wonder 5″ teams reeled off an incredible 88 – 8 record over his first four seasons and those teams laid the foundation for decades of sustained success by St. John’s basketball. A dominant fixture in the New York basketball scene, St. John’s currently ranks in the top ten all-time winningest college programs, ahead of such schools as Indiana and Louisville.

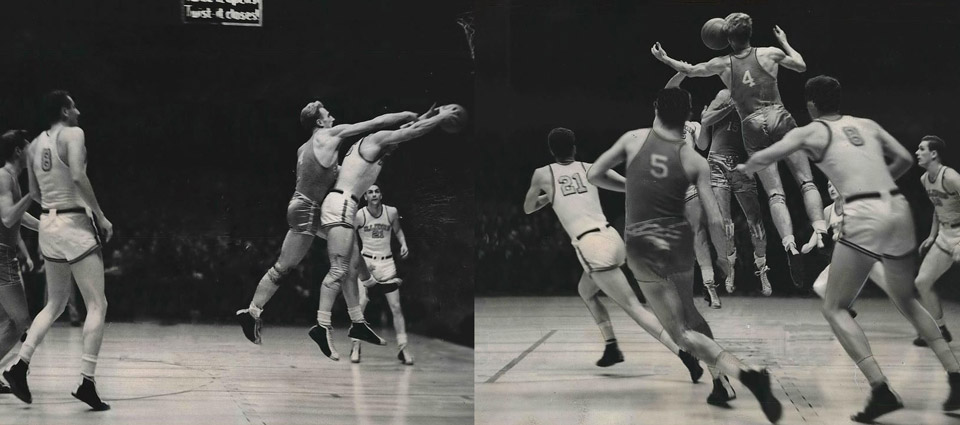

When Bush started his first season on the varsity squad for the 1935-36 season, Coach Freeman was in his final season. Bush quickly impressed during games at Madison Square Garden in the new Metropolian New York Conference and the St. John’s team finished with a 18 – 4 record. Games were very low-scoring and Bush averaged 6.2 points per game. He was a tough 6’3” forward that attacked the ball with reckless abandon as these series of rare photos below show (wearing #4):

The life and times of Curtis Bray

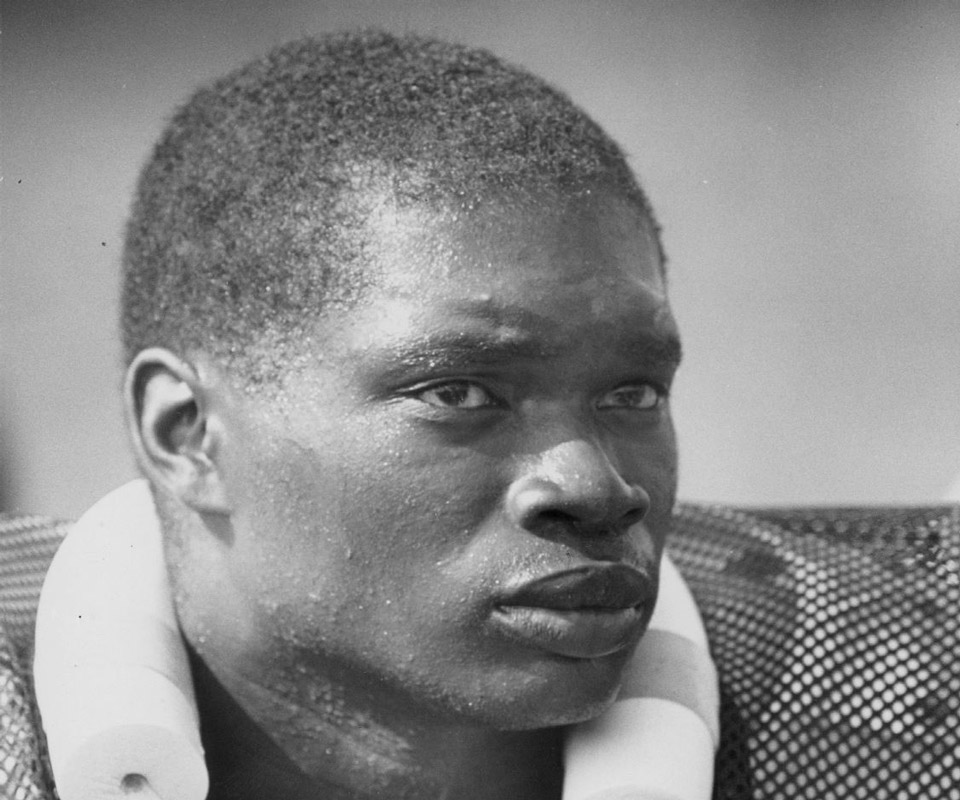

The Iowa State University athletic fraternity was rocked again recently with the tragic news of assistant football coach Curtis Bray’s death at the young age of 43. In the immediate aftermath, players and coaches mentioned Bray’s ability to mentor and teach life lessons to others. Many obituaries focused on his long coaching career, but Bray was also such a decorated prep athlete that he was Gatorade’s National High School Football Player of the Year in 1987-88. Digging further, I found more information about his high school and college experiences that helped define Bray’s “life coach” persona later in his career.

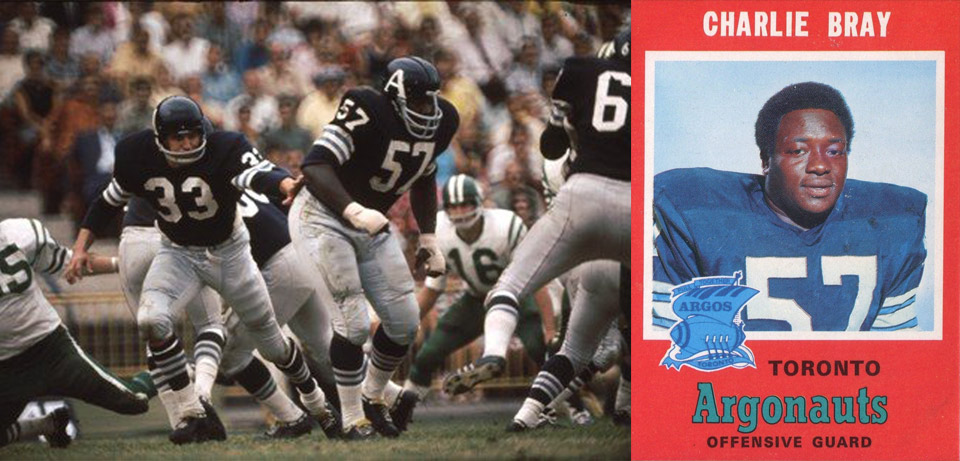

Curtis Bray was born in 1970 into an accomplished, athletic family. Bray’s father Charlie was an imposing man who enjoyed a professional football career as an offensive guard in various leagues, including six seasons with the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League, two seasons with the Memphis Southmen (better known as Grizzlies) of the World Football League, and a brief period with the New York Giants. During his stint with Toronto from 1968 to 1973, Charlie was named to the CFL All-Star team in ’69 and ’70. In 1971, after negotiations with the Miami Dolphins failed, quarterback Joe Theismann joined the Argonauts and stayed through the 1973 season. Together in 1971, Bray and Theismann led the Argonauts to their first Grey Cup championship game since 1952, although they would lose 14 – 11 on two critical fumbles late in the game–one which can be seen here. The game was also notable for being the first CFL game on artificial turf, which contributed to the traction issues seen in the video.

Early days of Johnny Orr

With the sad news of former Iowa State University coach Johnny Orr’s passing, I became curious about the brief references to his storied early days. It turns out Orr had a record-setting athletic career prior to entering coaching, where he became the winningest basketball coach at the University of Michigan and Iowa State University. The more I dug, the more interested I got. Perhaps the best place to start the story of John M. Orr is with his senior year at Taylorville High in Illinois, where he was part of an enthralling streak that captured the attention of the entire state.

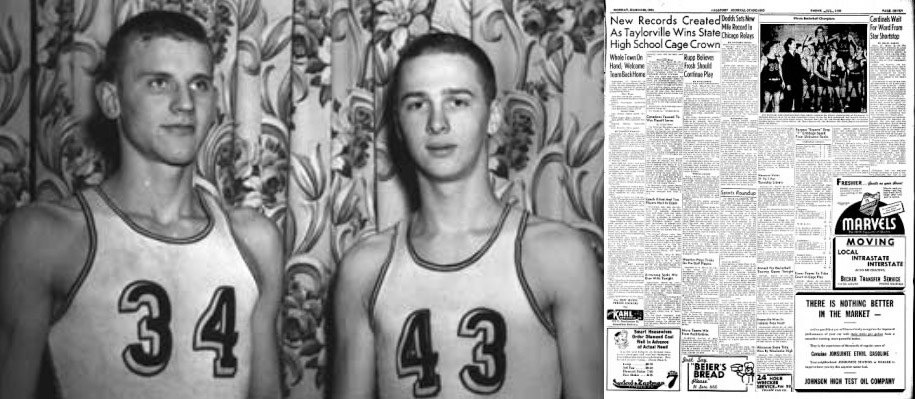

As World War II dominated the nation’s hearts, Orr’s senior year of 1943-44 saw him become an all-state player in football and star on the baseball diamond. Standing a strong 6’3″ tall, Orr’s best sport was basketball and in his last season, the Taylorville Tornadoes basketball team coached by Dolph Stanley was expected to be a tough out. Despite being a small school of just 566 students, the Tornadoes boasted two elite players: Orr and fellow lanky teammate Ronald Bontemps. Week after week, excitement slowly started building as they culminated a magical run through the Illinois high school basketball state tournament by becoming the first undefeated team in Illinois history. On their way to an incredible 45 – 0 record, Taylorville triumphed over other Illinois schools triple and quadruple their size. To this day, a large picture commemorating the 1944 championship hangs in Taylorville’s gym. (The basketball floor was recently named after Coach Stanley.) Orr can be seen in the front row wearing 43 next to Bontemps, who is wearing 34. Coach Stanley is in the top right circle.

As one of the smallest schools in the entire field, Taylorville’s squad impressed so much that both Orr and Bontemps were named to the all-tournament team. Orr finished as the second leading scorer in the entire tournament–just two points out of first–with 64 points in just four games–an average of 16 ppg. Bontemps was no stiff either with 49 points, good for fourth overall and an 12.25 ppg average. (The tournament’s leading scorer, Paul Schnackenberg of Chicago South Shore, became Orr’s teammate the following year in college.) The accolades poured in for the towering duo.

Collegiate Manufacturing Company of Ames

When I was in Ames this past summer, I became curious about the history of Collegiate Manufacturing Company after seeing the Cy costume created by them on display in the Iowa State Alumni Center. I didn’t realize that Collegiate’s role in Iowa State history went much deeper.

First, an aside: some people erroneously believe the original Iowa State teams were formerly known as the Cardinals, which has no basis in history. In a previous story, I shared the zany adventures of the 1895 Ames football team that earned the Cyclones nickname. Prior to 1895, references to the athletics teams of Iowa Agricultural College/Iowa State College were usually the “Ames eleven” or “Ames nine” (for football and baseball). I’ve also seen numerous reference to the “Iowa Aggies” since Aggie was a common nickname for many agricultural schools of the era formed by the Morrill Act in 1862. At the time the 1895 football team earned the nickname Cyclones, the school colors were silver, black, and gold. It wasn’t until 1899 that the school colors of cardinal and gold were established, well after the Cyclone moniker took root. As ISC grew through the 20th century, numerous organizations were established–such as the Cardinal Key in 1926–that took inspiration from the school colors. It wasn’t until the 1950s that a cardinal bird named Cy became the official mascot of Iowa State College.

In light of billion dollar TV contracts and apparel deals, many have cast a jaundiced gaze upon the rise of corporate influence in amateur sports–most famously with Nike and the University of Oregon. Nike has drastically changed the uniforms, facilities, and logo of Oregon in a quest for increased success and profitability. In recent years, Under Armour has attempted to mimic Oregon’s relatively new success by making the University of Maryland their flagship school. However, this isn’t a new trend. The close–but benign–relationship between Collegiate and Iowa State College gave birth to Cy.

Iowa State Digital Collections

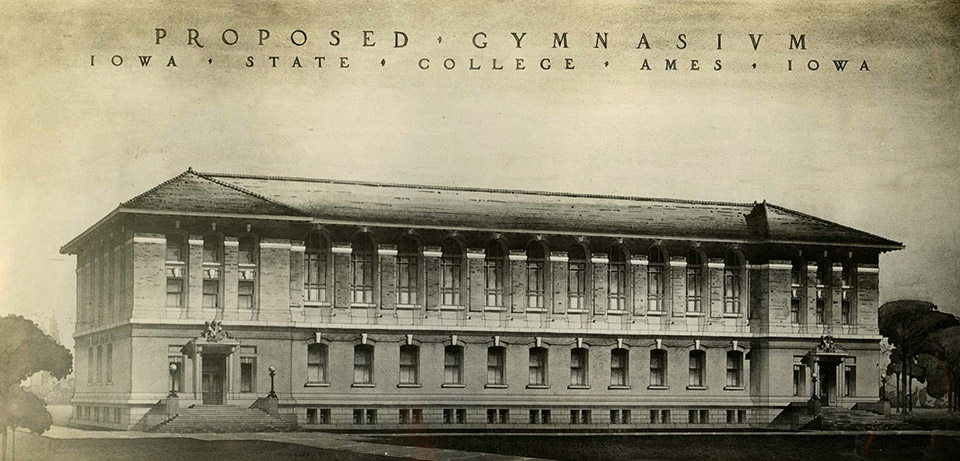

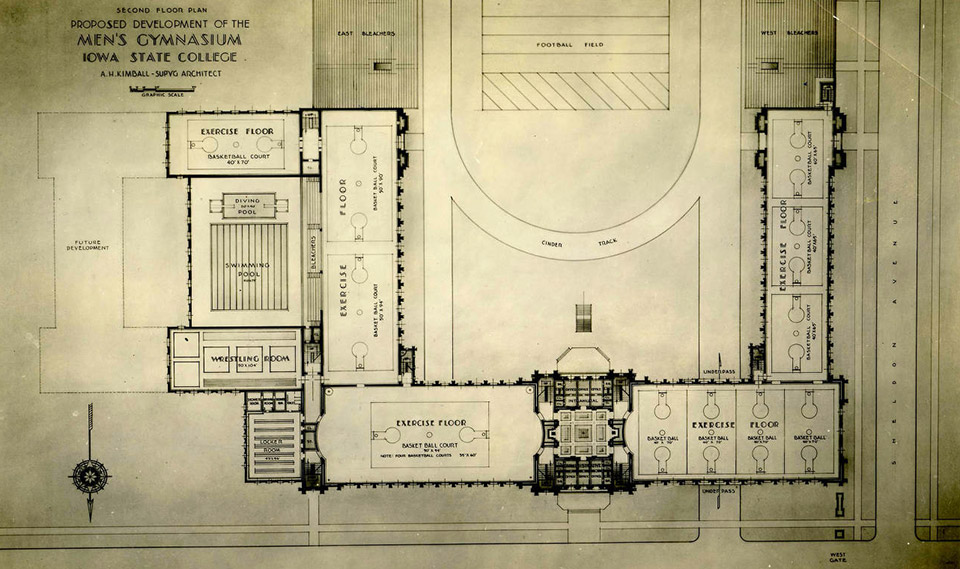

The Internet has made research vastly easier and the ever-expanding Iowa State University Digital Collections has helped me make some crucial connections while studying Cyclone athletic history. Athough some photos are mislabeled or have incorrect dates and there are still large gaps, I hope ISU keeps bolstering this archive because its an important look at Ames in the early days. In the meantime, here are a few of my favorite photos.

There are quite a few photos of State Gym in the collection. Look at two different proposed designs, which clearly didn’t get built.

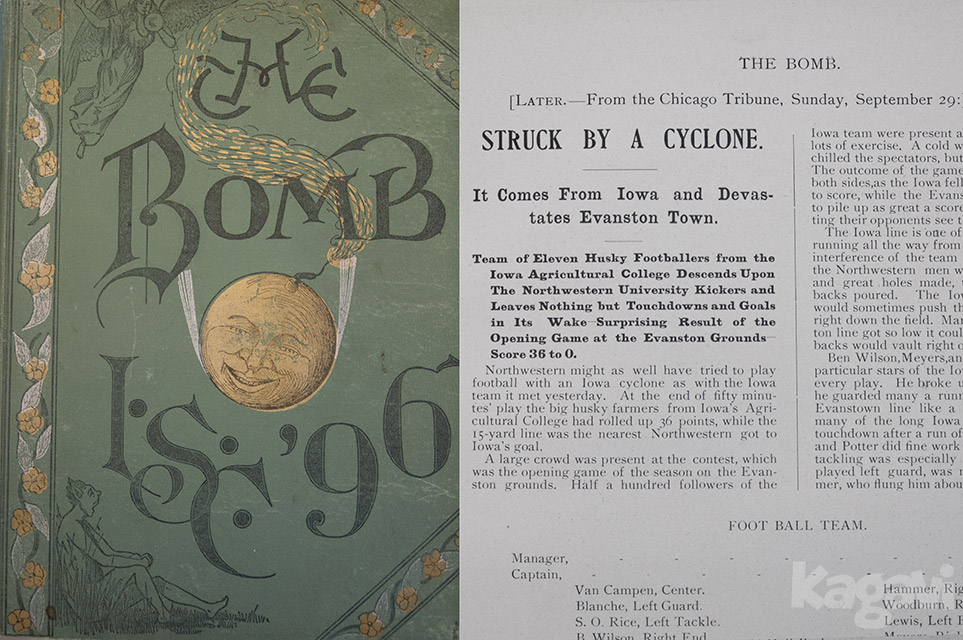

The original Cyclones

In 1858, Iowa State University was established as Iowa Agricultural College and the Cyclone nickname took root after a shellacking of Northwestern by the underdog Ames football team in 1895. Throughout the formative era of collegiate football, the Ames team experienced bed bugs, dubious referees, a train trip to Montana halted by snow and no food, and the agony of using hair as helmets. During this time, an unassuming black student named George Washington Carver helped the football teams as a trainer before eventually achieving worldwide fame with his scientific breakthroughs, inventions, and prodigious talents in the arts, which led Time magazine to dub him the “black Leonardo” in 1941.

The first Ames football teams played on the grassy space in front of the imposing turrets of Old Main that dominated the IAC landscape. A newly forged bell behind Old Main was used to ring class into session and enforce curfew. Later the bell would be appropriated by the football team at Clyde Williams Stadium and it currently stands near Jack Trice Stadium as the Victory Bell. Two fires in 1900 and 1902 destroyed most of Old Main, leading to its replacement Beardshear Hall. (Interestingly enough, the University of Arkansas has a very similar building, also dubbed Old Main, still standing.) The Ames Historical Society put together an extensive history of Old Main with many large pictures of the campus at that time. In the second picture below, find the bell behind Old Main and the Dinkey tracks.