Monthly Archives: November 2021

Jack Trice and the Ku Klux Klan

I am haunted by Jack Trice’s life and cannot stop thinking about his last days. Over the years, I’ve often mused on the role of the Ku Klux Klan in that era and searched for an answer that simply doesn’t exist. Many popular stories only mention the presence of the Klan in Minnesota when the Iowa State team arrived for their game. The reality is much messier and adds crucial context to Jack’s tragic letter.

We should first consider an obscure tale from Jack’s senior year in high school, which I initially found in 2014. At the time, I was researching why East Tech’s football team didn’t play in another championship game in 1921, but set it aside because I felt there was a bigger story to tell. It took several years for me to piece together the full story and the shocking truth served as an ominous harbinger of events to come.

Two years later, the Ku Klux Klan sealed their presence in Ames. This is the untold story.

_____________

In high school at East Tech, his wide eyes drinking up the city around him, Jack saw very quickly Cleveland wasn’t the small country village he grew up in. Custom dictated withdrawal here. The Great War whisked up East Tech students and they learned what burning flesh smelled like on the Western Front. Back home, the Spanish Flu took ragged bites out of America. Bodies piled up.

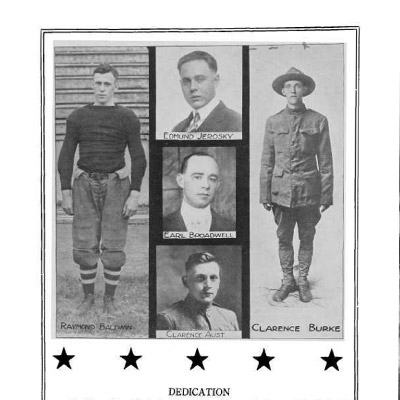

East Tech made sure no one forgot the sacrifice of those who never returned.

In 1920, Jack was one of several junior players who helped East Tech polish off an undefeated regular season that culminated with a bid to the prep national championship game in Washington–a game I previously wrote about. The boys rode the rails for a week and bonded on the trip. They played cards, sang, and giggled their way through spectacular western landscapes.

During Jack’s senior year, East Tech didn’t miss a beat, rolling to another undefeated season. The papers praised his play far and wide. He had come a long way and was one of the best players in the country, a colossal talent. In addition to his suffocating play on the line, he played some at fullback and shared punting duties. He could do it all and nothing could stop him.

Opposing fans took umbrage. They lashed out in anger and hurled insults. After one emotionally charged game that ended in victory, Jack was called a “monkey.” He always had to live with the implicit threat of bloodshed lurking in the shadows. When another high school was clobbered by East Tech, they offered an interesting cartoon recap of the game. Note the mysterious figure in the background.

The postseason beckoned. This time, East Tech would bring the crown home. Schools across the country clamored for a shot. Anticipation teemed.

Negotiations started with a New England school. One school in Minnesota wanted a game on Christmas Day. All potential games fell through, but in mid-December, East Tech agreed to meet Bryan High in Texas for the national championship. Texas was Klan country and the game would be held about 80 miles southeast of Waco, where the infamous torture and lynching of Jesse Washington occurred in 1916.

It was not to be.

When it became understood that Jack, the dread black phantom, presented a problem, his white teammates rallied around him and unanimously voted to give up the trip and their last shot at the national championship. One teammate said, “He gave us the best he had–we owe it to him.”

The Texas papers didn’t handle it well, fuming about the “nigger” who ruined the big game. One celebrated writer invited his readers to share in delightful imagery. Why not have Jack play in the big game before the crowd of thousands? After all, they would make sure he was carried off dead.

It would be nearly two years before Jack played in a big game again–the one that killed him.

_____________

When Jack arrived in Ames, the Klan was already around him. Local papers speculated on how many people would join the organization. One nearby town reported Klan posters were “found in the police office, altho no one was able to explain how.” In communities across Iowa, Klan envoys brought gifts to homes, hoping to win favor.

A couple of years ago, I returned to Ames and met with Alex Fejfar, the Exhibits Manager of the Ames History Museum. The museum is a small gem directly across the street from the Masonic Temple where Jack had his last words with his wife Cora Mae before the Minnesota game.

With Alex as my guide, we rooted through the Masonic Temple basement, peering through the dust of decades, looking for any elusive sign. On the top floor, we retraced steps of long ago and breathed in the memories. In one remote staircase, we were trapped by a locked door closing behind us. It seemed, just perhaps, the ghost of Jack Trice was guiding us.

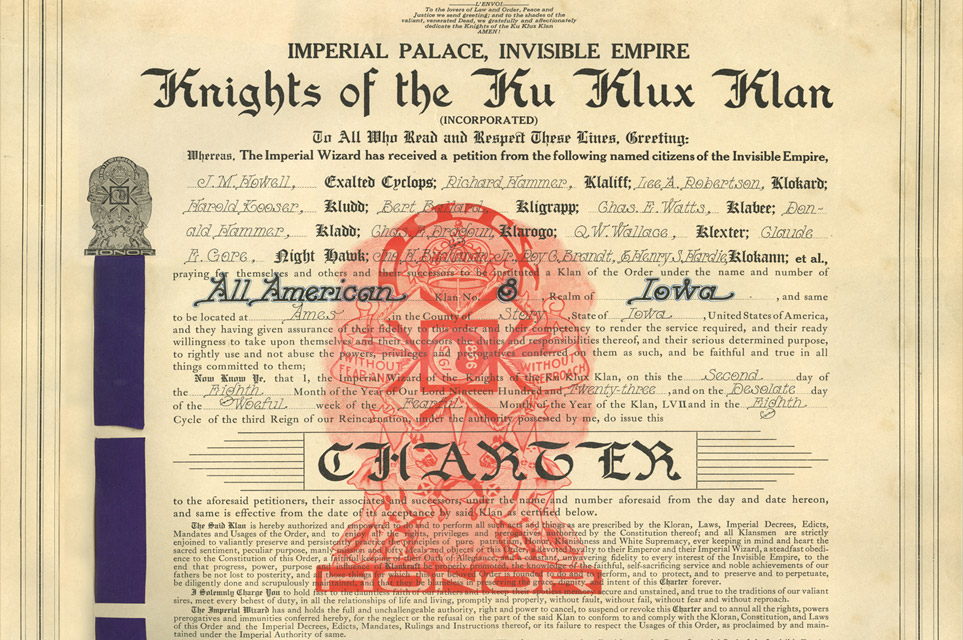

My list of research questions was immense and we had so little time. Back at the museum, Alex dug through the archives and presented a chilling example of hate so close to home. Thanks to the “Private Collection of Jerry Litzel, Courtesy of Ames History Museum,” we are able to present it here.

In August 1923, awash with patriotic faith in their country and flag, thirteen Ames men stepped forward to enshrine their names on the Ames charter of the “Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.” These men knew they were destined to be “All American” leaders of the Klan “Reincarnation.” Some time later, the Imperial Wizard, Hiram Evans, signed it. The ceremony was complete.

It didn’t take long for the crosses to start burning.

Less than a month later, the Nevada Journal reported a fiery cross was burned on the edge of town as the Ames Klan attempted to intimidate an accused bootlegger. Their presence was impossible to deny any longer. Membership swelled. More crosses were burned. Prominent Ames citizens took pride in their leadership role, including those who walked the Iowa State campus. Unbeknownst to some students they were taught by the Klan, including a very small and real possibility that Jack was among them (which I’m still researching).

Black students at Iowa State were barred from living near campus, so they usually ended up in downtown Ames near the Masonic Temple. Some worked at the Sheldon-Munn hotel. Unfortunately for them, Klan meetings were often held downtown. Members of the hooded order prowled near where Jack and Cora Mae held each other on lonely nights.

Something had to be done.

_____________

Before Jack was a blank piece of Curtis Hotel stationary on the small desk. He was going to be the only Black player on the field against Minnesota. Hundreds of years of anguish and pain flowed from his pen. He was surrounded by hate and carried the burden of all before him. Those who were lynched without a thought. The bottomless eyes of white hoods. Flickering flames reaching high. The game was tomorrow and it was already too late.

“The honor of my race, family, and self are at stake.”