How the first Black individual Olympic champion came off crutches to win gold

How the first Black individual Olympic champion came off crutches to win gold

DeHart Hubbard was intent on making history. That he did so while injured made his achievements even more remarkable

_____________

DeHart Hubbard knew about the jinx waiting for him.

Hubbard was a student at the University of Michigan and regarded as one of the best long jumpers in the world. Heading into the 1924 Paris Olympics, he was America’s best hope for gold in the long jump and favored to become the first Black athlete to win an individual Olympic gold medal.

Hubbard started writing.

Dear Mother: At last I am ready to depart for Europe. It has taken years of hard work to get this far, but I am nearing my ultimate goal.

He had to hurry. The boat was about to leave for France. He turned the page and his words ran and jumped across the page, leaving no doubt.

I’m going to do my best to be the FIRST COLORED OLYMPIC CHAMPION.

He underlined the last four words, but made sure to underline “COLORED” twice. His impending victory would be for his people.

_____________

At Walnut Hills High School in Cincinnati, Hubbard discovered his innate talent. Word got out about the kid with springs for legs. Under the tutelage of Hunter Johnson, a pioneering Black trainer in Pittsburgh, Hubbard tried to make the 1920 Olympic team. He was 16 and eager, but “trained too hard” and his body broke down. Back home, he started thinking about breaking the long jump world record. It became an obsession.

The University of Michigan’s head track coach, Steve Farrell, was widely respected. He had been a circus performer and professional runner during the 1890s and he understood the demands of competing at an elite level. When Hubbard arrived at Michigan in 1921, Farrell promptly barred him from other sports and had him focus only on jumping events. Hubbard started jumping past 25 feet, flirting with the world record, which stood at 25 ft 2 3⁄4in (7.69 m) in 1921, and he qualified for the Paris Games in the long jump and triple jump.

_____________

On 16 June 1924, the SS America departed from Hoboken, New Jersey, with more than 350 athletes, coaches, trainers, and officials aboard. Foghorns blared and fireboats sprayed water high in the sky, the sunlight glinting in the mist. On the dark hull, AMERICAN OLYMPIC TEAMS was painted in enormous white letters, easily visible from a distance. The steamship glided past the Statue of Liberty on the way to Cherbourg, France.

During the long voyage – the coaches thought too long – Hubbard and his fellow athletes jostled for space to train. Swimmers swayed in the tiny canvas pool, water slopping over the sides. Runners navigated tight curves on the deck. Javelins and shots ended up in the ocean. When they arrived on 25 June, fellow track teammate William Neufeld remembered the young male athletes couldn’t wait for the “beautiful French girls” who would “greet us with flowers” and a “kiss on each cheek,” but it was raining and they were welcomed by a “bunch of bearded men” instead.

After reaching Paris, Hubbard and most of the squad ended up at a chateau in Rocquencourt, near Versailles. It belonged to the fifth Prince Murat, whose ancestor had married Napoleon’s sister. Majestic chestnut and yew trees hugged winding paths. Sphinx sculptures guarded the gorgeous rose gardens. It was wonderful – and the team hated it.

They lived in slapdash barracks, 11 in all, made out of flimsy pressboard. The army cots were hard, the food “indifferent.” Peddlers roamed the grounds, trying to sell jewellery to athletes in the middle of workouts. In order to reach the Olympic stadium in Colombes, they were forced to ride “busses with hard tires” into thick Paris congestion, banging and rattling over rough cobblestone roads while covered in dust. The journey took a hour, sometimes longer, and was miserable.

_____________

During training at the Olympic stadium, some runners complained about the soft track surface and the “cupping” that was created by their feet sinking down too much. At the long jump pit, Hubbard noticed something odd. The takeoff board was backwards. The worn, curved edge was facing the pit and the crisp edge was now pointed at the athletes.

Observers watched Hubbard work through his paces, practicing height, not distance. One reporter wrote he was “the centre of attraction for a number of French enthusiasts.” Hollywood star Douglas Fairbanks, a noted track nut, was on hand as well.

They were impressed by Hubbard’s blazing quick start and chiseled calves. The US team’s head track coach, Lawson Robertson, said he had “that zip and pep of the nervous champion” and was “the perfect athlete.” Another remarked that Hubbard flew over the track so quietly, “you couldn’t hear him. Pit, pit, pit, pit, pit. Not a thumping sound, but quick, quiet steps.”

_____________

The night before the long jump competition, Hubbard was staying at the Olympic Village in Colombes, working on a picture puzzle to relax when two men burst into the hall with shocking news. While competing in the pentathlon, fellow American Robert LeGendre had just broken the long jump world record with a leap of 25ft 6in (7.76m).

Hubbard was stunned. The world record was his obsession and everyone knew it. He later wrote that he “tried to appear unconcerned, but made a poor job of it.” Coach Robertson wasn’t fooled and said “his color turned white.” LeGendre had dealt Hubbard a psychological blow. Sleep was impossible and he wasn’t “in the best of shape the next day as a result.”

_____________

Tuesday 8 July was a beautiful afternoon. Hardly any wind. Low 70s fahrenheit. The stands were full of American fans cheering their boys. On the field, more than 30 long jumpers gathered, representing 21 countries.

For his first jump, Hubbard didn’t want to simply qualify for the finals, he wanted to erase LeGendre, who only competed in the pentathlon in Paris, from his mind. He stood at the start of the runway, wearing thin sprinter spikes with “sponge rubber in the heel” instead of jumping shoes that he felt were too bulky and stiff.

But he didn’t know there was a problem. The soft cinder surface had developed a small hollow, perhaps a “quarter of an inch or half inch” in front of the takeoff board. With the crowd watching, he charged down the track, the record in sight. His right heel slammed against the exposed hard edge of the board at full speed.

The jump was a foul and he could barely walk. He thought “of the jinx that had always trailed Negroes in the Olympics.” Over the years so many before him had come close to glory before suffering an injury. In the 1920 Antwerp Olympics, fellow American long jumper Sol Butler was favored but suffered a pulled leg muscle and had to be carried off the field. Now Hubbard “was fearful it was about to happen to me.”

His second jump was a disaster. He fell backwards upon landing “for the first time in my career, losing more than a foot.” He couldn’t make any more attempts to qualify for the final and was carried inside. The pain was becoming worse. While the trainers worked on his injured heel and wrapped it, he discovered he had somehow squeaked through to the finals in fourth place.

Before the final, Hubbard was “hobbling around” the field with crutches. Robertson was on the verge of taking him off the team, but he “begged for a chance … I didn’t have the heart to keep him out.” Since Hubbard couldn’t put pressure on his heel, he would have to jump using only his toes.

For his final jump, Hubbard envisioned “all my race looking at me to make good” and he let his emotions build into a powerful tailwind. He shot down the cinder runway, kicked through the air and landed perfectly. He cleared 24ft 6in (7.47m) – nowhere close to LeGendre or his own standard, but good enough to win (John Taylor, another Black American athlete, had won team gold at the 1908 Olympics in the medley relay).

Robertson was shocked by Hubbard’s victory and felt it wasn’t possible to jump so far without pushing off the heel: “I thought that some mistake was made in the distance … I went up to the judges and asked them if the jump was right.”

As the band played The Star-Spangled Banner and the American flag rose up the pole, Hubbard realized it was “the first time a colored American had put one there. I didn’t break the record, but I was pretty happy that night.”

He spent the rest of the Olympics on crutches and withdrew from the triple jump. The injury lingered for another year.

_____________

Back home in Cincinnati, a local reporter met with Hubbard’s wife Marion and their infant daughter. She expressed her happiness but asked for “some tolerance, some kindliness, some justice” for Black people instead of “parades and brass bands and feasts.”

After the Olympics, Hubbard entered his athletic prime. He tied multiple world records in sprint events. In his last meet for the University of Michigan in 1925, he finally achieved his ultimate goal with a new world record in the long jump by jumping 25ft 10 7/8in (7.89m). It marked the 10th time Hubbard had jumped over 25ft. No other athlete had done it more than once.

In 1927, he became the first man to jump over 26ft, but the AAU controversially refused to certify it because the meet referee estimated the sand was perhaps an inch too low. That jump wouldn’t be surpassed until Jesse Owens leapt out to 26ft 8in (8.13m) in 1935.

Some months later, Hubbard severely injured his ankle in a volleyball match, which ended his chances of repeating at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics. He would never have another chance at an Olympic medal.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Hubbard worked for the Cincinnati recreation department and also founded the Cincinnati Tigers Negro baseball team and starred in other sports. Harlem Globetrotters visionary Abe Saperstein once said “If DeHart had gone into basketball, he would have been one of the five best of his time. If he had gone into baseball, he would have been one of the five best.” Hubbard later joined the Federal Housing Administration in Cleveland and worked with Jesse Owens and other former elite Black athletes. They often talked about the old days of gold medals and laurel wreaths.

_____________

(Originally published by The Guardian and edited by Tom Lutz.)

Coney Island Was Once Full of Dueling, Backstabbing Theme Parks

Coney Island Was Once Full of Dueling, Backstabbing Theme Parks

Come one, come all to the controversial, ugly beginnings of what was once called ‘Sodom by the Sea.’

_____________

Coney Island was once a glittering star of the early 1900s. It was the Progressive Era, amusement parks were becoming enormously popular across America, and New York City’s version of roller coasters and carnival games seemed like the epitome of wholesome fun. But the beachy entertainment land was quite different than it is today. Coney Island mainly consisted of three theme parks: Steeplechase Park, Luna Park, and Dreamland. And from 1904 to 1911, all were locked into a perpetual dance of stealing acts, copying rides from each other, and some dirty competition.

This fleeting moment in time was captured by a little-known Brooklyn artist named John Mark. His rare 1906 “bird’s eye view” map was full of spectacular details at the three competing parks. Together, they helped turn around the reputation at Coney Island—which was once considered tawdry and called “Sodom by the Sea”—bringing clean fun to families.

“Coney Island was a laboratory for the invention and testing of social, commercial, and technological ideas,” says art historian Robin Jaffee Frank, who authored the book and curated the exhibition Coney Island: Visions of an American Dreamland. “Coney Island revolutionized the way people played.”

It all started with Steeplechase Park, which first opened in 1897. Founder George Tilyou was a popular figure in the area, and people knew his “Funny Place” was full of laughter. Guests rode his Ferris wheel and galloped around his celebrated Steeplechase horse ride. Amusing and frugal diversions were everywhere. Tilyou’s haunting cartoon visage, full of teeth and horned hair, became an icon still used today, known as “Funny Face.”

Tilyou often toured the country looking for ideas. At the 1901 Buffalo Pan-American Expo, he saw future Luna Park founders Fred Thompson and Skip Dundy and their popular “A Trip to the Moon” attraction. Designed by Thompson, guests boarded a futuristic Victorian spaceship and bumped their way to the colorful moon, where they walked among strange lunar creatures.

Tilyou was smitten. He lured them to Steeplechase in 1902 with promises of a significant share of profits—but it came with a risk. “Tilyou recognized that by securing ‘A Trip to the Moon’ for Steeplechase, he was inducing a future competitor to enter the field,” says historian Michael Immerso, author of Coney Island: The People’s Playground. The duo also brought their popular “Giant See-Saw” ride, which lifted people hundreds of feet in the air while seated in a rotating wheel at each end.

Much to Tilyou’s regret, Thompson and Dundy immediately started making plans for Luna. Prior to moving to the new park, they clashed over the seesaw. Tilyou wanted it. Thompson and Dundy wanted it—or money. Back and forth they went, like the seesaw. Dundy finally proposed an absurd bet. Tilyou could flip a nickel, and if he won, he could have it for free. If he lost, he would pay Thompson and Dundy $12,500 to keep it. Tilyou flipped and paid nothing.

Luna Park therefore opened in 1903 and made an immediate impression on the public. Luminous lights swirled around the park, punctuated by the brilliant Electric Tower easily seen across the island (which eventually became a peninsula using landfill). A boisterous spirit and fantastical architectural elements transported people. There were miniature trains and elephants. “A Trip to the Moon” kept the guests coming. Luna made Steeplechase look outdated by comparison.

“Luna Park served as a template for every amusement park that followed,” says Immerso. “Thompson was an exceptional choreographer. Every component of the park, visually and by sensory means, played a part in creating a singular and enchanting environment.” The partners were a perfect fit for each other. Thompson’s boyish spirit created the attractions, and Dundy was the financial whiz. But their partnership almost didn’t happen.

In fact, the two had already become well-acquainted with ride stealing, as that’s how the unlikely duo partnered up.

Leading up to the Buffalo expo—where Tilyou first saw them—Dundy had been impressed by an attraction that Thompson created for another fair. Dundy wasted no time and quickly scampered to Buffalo to shamelessly propose Thompson’s popular “Darkness and Dawn” as his own idea. Once Thompson realized his unpatented ride had been stolen, he tried to strike back with his own version. It became ugly. Fellow showmen started placing bets on who would get the coveted concession spot. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported, “Dundy knew a thing or two about the manipulation of sub-surface wires, and when the concession was awarded, he won in a walk.”

Rather than swear endless vengeance, Thompson couldn’t help but be impressed by Dundy’s audacious display. He had seen nothing like it before, so he magnanimously told Dundy about his gestating “A Trip to the Moon” idea and said they should work on it together instead, which they did. Although the Buffalo fair was a financial flop, their innovative experience was one of a few to make money, and it became a key part of Luna’s revenues for many years.

The parks were not beyond putting humans and animal suffering on display. During the construction of Luna, Thompson and Dundy acquired an elephant named Topsy but soon tired of her behavior and expense. For promotional purposes, they controversially electrocuted her in front of media members and a “moving picture” camera. The lurid newsreel still survives.

Villages of Indigenous peoples were a popular fixture at fairs across the country, put on display for European descendants to stare at. In 1905, Thompson and Dundy took note of a particular group of Indigenous people from the Philippines, which promoters called “Igorrotes,” but who were actually Bontoc people. The owners wanted the same act. Signed contract in hand, the “Igorrotes” became a star attraction at Luna. The owners and press spread the idea that spectators could watch them feasting on dogs in what was typically a staged act forced upon them. It was an “Imperialist fantasy on display,” which “enforced a racial interpretation of hierarchy, expansion, and exclusion,” according to the Coney Island Museum.

Yet Luna was considered an exemplary theme park of the time. Seeing its success, a man named William Reynolds saw dollar signs and wanted in. The slippery, former state senator was also a real estate magnate (who was later indicted for hiding his ownership in condemned property and stealing city funds). In 1904, he opened a competing theme park called Dreamland. It was a glowing white city by the sea that cost millions and targeted the genteel set. He wasn’t a born showman, so he ripped off as many attractions as he could and made them more grandiose.

Dreamland’s enormous electric tower was covered in 100,000 twinkling lights. They copied Luna’s Shoot the Chutes water flume ride, but added an extra track and planted the towers in the ocean. Luna had a disaster show called Fire and Flame, so Dreamland had their own version called Fighting Flames, which was more elaborate. The groundbreaking infant incubator display at Luna was replicated. Reynolds laughed at the meager ballrooms found at Steeplechase and Luna. His huge ballroom sat on his pier above the Atlantic Ocean.

Despite Dreamland’s opulence, Luna remained more popular. So Reynolds told his general manager to do whatever was necessary to drum up business. Operating in secrecy, Dreamland promised the Filipino community at Luna better working conditions and more money, and convinced them to leave the former park for the newer one. Thompson and Dundy were furious but tried to save face by absurdly claiming they closed the exhibit because they didn’t want to exploit the Bontoc people.

In 1907, the year after Mark’s map was created, Steeplechase was destroyed by fire, but Tilyou soon reopened. That same year, Dundy unexpectedly died and Thompson started a slow descent into bankruptcy. Dreamland was burnt to a crisp in 1911, and Reynolds never rebuilt. The golden era was over.

The theme parks of Coney Island continued to evolve over the next few decades, with Deno’s Wonder Wheel built in 1920 and the Cyclone roller coaster opening in 1927. Though the original Luna Park closed during World War II, an unrelated Luna Park opened in a different location on Coney Island in 2010, where it’s in operation today. Few remnants of the original three parks survive, but replicas of Tilyou’s iconic “Funny Face” can still be seen here and there. Both the Coney Island History Project and the Coney Island Museum have artifacts from previous eras on display.

As for the map, it is only known to have appeared in two small classified ads in a local newspaper. In one, the artist offered his Coney Island “Souvenir bird’s eye view” map for a dime and suggested people could “Mail It to Your Friends.” The other asked for the “greatest seller” to peddle his maps for “100 per cent. profit.” Afterwards, the artist faded from view and the map became lost to time, yet remains on record as a snapshot of Coney Island’s foundational, backstabbing theme parks.

_____________

(Originally published by Atlas Obscura and edited by Danielle Hallock.)

How secrecy and betrayal led to the creation of Mickey Mouse

How secrecy and betrayal led to the creation of Mickey Mouse

After Walt Disney’s friends betrayed him, he scrambled to stave off bankruptcy with a mouse cartoon that’s now in the public domain.

_____________

In May 1928, at a movie theater on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, the crowd was treated to an unannounced preview of a new silent cartoon from a local studio. The viewers had no idea they were witnessing the birth of a global phenomenon.

The single reel started to roll, and the screen flickered. The organist began to play. A dark screen appeared with the title “Plane Crazy” in white letters. The audience met a black mouse as he attempted to become an aviator.

A young man named Walt Disney nervously watched their reaction.

This preview, on May 15 (or possibly a bit earlier, according to Disney historian J.B. Kaufman), marked the beginning of Mickey Mouse — and the end of a frantic two months of betrayal and secrecy while Walt struggled to save his company.

‘Everybody was conspiring’

In 1927, the Walt Disney Studio was surrounded by scrub and scraggly hills in a quiet area about four miles northwest of downtown Los Angeles. Walt was the relentless creative force, and his brother Roy was the widely respected finance whiz. Walt’s close friend, Ub Iwerks, was his lead animator. They had a long history stretching back to Kansas City, Mo., where they first learned the business together.

“Oswald the Lucky Rabbit” — Disney’s new series created for Universal Studios — was becoming a hit across the country. Oswald was controlled by Disney’s longtime distributor in New York, Charles Mintz, with whom Walt had a prickly relationship. Walt didn’t know Mintz had betrayed him, with the help of his good friends.

In mid-1927, Mintz’s brother-in-law, George Winkler, who managed his operations in Los Angeles, started lingering longer at the Disney studio. He was arranging clandestine meetings with Walt’s animators and planning to launch a rival studio to assume production of Oswald.

Mintz and Winkler targeted Hugh Harman, a young Disney animator who had worked with Walt back in Kansas City but had grown tired of his overbearing pressure. Harman jumped at the opportunity to take Oswald away from Walt. Unbeknownst to all of them, Harman also had his own secret shop and was developing a new character.

As the year came to an end, more animators were recruited to join Harman, and they were close to officially signing with Mintz to keep creating Oswald cartoons. One animator said it was an era when “everybody was conspiring against the other one.”

In February 1928, Walt and his wife, Lillian, took a “second honeymoon” via train to New York, where he was scheduled to meet with Mintz to negotiate a new annual distribution contract for Oswald. Walt wanted to increase his fee from $2,250 to $2,500 per cartoon. But weeks of negotiations went nowhere — and he learned he was on the verge of losing much of his studio to Mintz.

Thinking quickly, Walt asked Roy via an urgent telegram to sign their animators to binding contracts, but most refused. Walt knew it meant “only one thing — they are hooked up with Charlie.” After several futile attempts to bypass Mintz or interest another studio in New York, Walt admitted defeat. Oswald was gone, along with most of his animators.

A frantic scramble

Back home in Los Angeles, Walt and Roy still had to work with the defecting animators to complete the last remaining Oswald cartoons by May. Money was running out, and they had nothing lined up to replace Oswald.

But Walt still had Iwerks. Together, they started developing a secret new animal character. Mice were a familiar sight in cartoons of the period, including the Disney shorts. Walt’s initial mouse concept was too wiry, and Iwerks changed it to a more pleasing round shape.

At first, they named it Mortimer Mouse, but Lillian vetoed the name, so they chose Mickey Mouse instead. Walt infused him with a bit of Charlie Chaplin, while Iwerks added the charm of the silent film star Douglas Fairbanks. Borrowing from a previous Oswald short, “The Ocean Hop,” they quickly created a rudimentary plot based around aviator hero Charles Lindbergh.

At the studio, Iwerks hid from the other animators — either in a locked room, according to Iwerks; or behind a black curtain, according to Harman — and animated the entire cartoon nearly by himself in mere weeks. Iwerks was already known for his speed and skill, but for “Plane Crazy,” he drew an incredible 700 frames a day, which he claimed broke a record held by a prolific New York animator. The average animator was lucky to get a couple hundred on a good day.

Starting in mid-April, Walt and Roy snuck Iwerks’s drawings to Walt’s nearby house, which had become a shadow studio. In the garage below the living room, Lillian — who had formerly worked as an inker for the studio — enlisted Roy’s wife and two or three other women to ink and paint Iwerks’s work.

“We worked night and day” to keep up, Lillian remembered, and “had a major budget crisis one night when I tripped on the garage stairs and ruined my last pair of silk stockings.” The women kept inking and painting at the kitchen table and “ate stews and pot roasts, which luckily were cheap,” Lillian said. Roy helped wherever he was needed, and Walt crept back to the studio at night and had the finished cels photographed.

The completed “Plane Crazy” short showed an unrefined Mickey harassing Minnie before ultimately crashing his plane. It concluded with an innovative shot that showed the view from the cockpit of Mickey’s airplane as it spiraled to the ground.

In a 1973 interview, Wilfred Jackson, a longtime Disney animator and director who was hired by Walt during the “Plane Crazy” production, said the shot “took days and days and days.” According to Jackson, they put a painting of the ground on a bed, then put shims under the bed “and raised it up a fraction of an inch, and shot another frame, and turned it just a little bit” and repeated, causing the painting to move closer to the camera as it rotated.

When they saw the finished scene, “we almost wore the film out,” Jackson said, “admiring what we had done.” It was a reminder of the talent still on display at Walt Disney Studio.

At the premiere of “Plane Crazy,” the “reception was good, though not overwhelming,” wrote Bob Thomas in “Walt Disney: An American Original.” After creating a second Mickey cartoon, “Gallopin’ Gaucho,” Walt simply couldn’t get anyone interested in distributing them.

With bankruptcy looming, Walt headed back to New York in the fall to try something else: adding sound to Mickey’s third cartoon, “Steamboat Willie.” After “Steamboat Willie” swept the country, Walt converted his first two Mickey cartoons into sound versions in 1929.

Along with “Steamboat Willie,” the silent versions of “Plane Crazy” and “Gallopin’ Gaucho” entered the public domain this year, meaning they can be shared by anyone on any platform and all audiences can now see the cartoon that first captivated viewers 96 years ago this month. The sound versions will join the public domain next year.

_____________

(Originally published by The Washington Post and edited by Aaron Wiener.)

How the Memory of a Song Reunited Two Women Separated by the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

How the Memory of a Song Reunited Two Women Separated by the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

In 1990, scholars found a Sierra Leonean woman who remembered a nearly identical version of a tune passed down by a Georgia woman’s enslaved ancestors

In 1933, the pioneering Black linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner met an elderly Gullah Geechee woman named Amelia Dawley in a remote coastal village south of Savannah, Georgia. While Turner recorded, Dawley sang a song of unknown origin, passed down through the generations by her ancestors. Dawley didn’t know the song’s meaning, but a Sierra Leonean student who heard the recording recognized its lyrics as Mende, a major language in his home country. Turner published an English translation of the song in his 1949 book, Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect.

Decades later, anthropologist Joseph Opala came across Turner’s work. He eventually decided to travel through Sierra Leone with ethnomusicologist Cynthia Schmidt and native linguist Tazieff Koroma in an attempt to trace the provenance of the mysterious lyrics. After a long, fruitless search through humid country, Schmidt ended up in the isolated village of Senehun Ngola, where she met a local woman who had preserved a shockingly similar song that traced back hundreds of years.

“[Her] grandmother had taught her the song, and she had kept it alive by changing the words for other occasions,” says Schmidt.

Located on the Windward Coast of West Africa, the region now known as Sierra Leone was a key player in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Westerners also referred to the area as the Rice Coast; as English abolitionist Thomas Clarkson wrote in 1788, the red rice found there was “finer in flavor, of a greater substance, more wholesome and capable of preservation, than the rice of any other country.”

When slave traders arrived in Sierra Leone, they found a lush country of verdant forests, knobby mountains and waters thick with aquatic life. Cultivated rice fields and wild indigo sprawled across the landscape. Massive mangrove trees crowded the riverbanks, rendering certain villages “scarcely perceptible” and protecting their inhabitants from potential enslavers, who could pass “within a few yards of a town” and not suspect anything, wrote English physician Thomas Masterman Winterbottom in 1803.

Bunce Island, where captive West Africans were held in a stone fortress before being forced onto slave ships for the deadly journey across the Middle Passage, served as the center of the region’s slave trade. In 1791, Anna Maria Falconbridge, the wife of an English abolitionist, wrote about the unforgettable “sight of between two and three hundred wretched victims, chained and parceled out in circles, just satisfying the cravings of nature from a trough of rice placed in the center of each circle.”

In North America, wealthy rice planters whose plantations lined the Lowcountry—a region along Georgia and South Carolina’s coast that includes the Sea Islands—paid a premium for enslaved people from Sierra Leone. When slave ships docked, local newspapers reported their arrivals and made sure readers knew the enslaved people on board were from a part of Africa famed for its rice cultivation. A 1785 advertisement published in Charleston, South Carolina, for example, touted the sale of “Windward Coast Negroes, who are well acquainted with the culture of rice, arrived from B[u]nce Island.”

Between about 1750 and 1800, the slave trade brought thousands of West Africans to the Lowcountry, whose Sea Islands resembled the marshes of their homelands. These individuals’ diverse languages melded together, and a distinctive patois and culture started to emerge. Known as the Gullah Geechee, the community has preserved remnants of its African heritage through food, rituals and art—including Dawley’s ancestral song.

_____________

Turner, the scholar who first recorded Dawley’s melody, counted Zora Neale Hurston among his students. The Harlem Renaissance author later remembered Turner as the professor “who most influenced me,” a handsome, soft-spoken “Harvard man [who] knew his subject.”

After a chance conversation with two students at what is now South Carolina State University, where he was teaching summer school in 1929, Turner decided to focus his fieldwork on Gullah language and culture. Walking along the Lowcountry, Turner interviewed descendants of the enslaved, made careful notes about their dialect and songs, and took photos. Turner’s first wife, Geneva Townes Turner, helped him record Gullah sounds and even enrolled in phonetics classes to prepare for the research.

Musicologist Lydia Parrish, who was also studying the music of the formerly enslaved, drew Turner’s attention to Dawley’s song. In the summer of 1933, he met 52-year-old Dawley and her 11-year-old daughter, Mary, in Harris Neck, Georgia. Dawley told Turner about a song passed down by her paternal grandmother, Catherine, who had survived the Middle Passage and was enslaved by a Georgia plantation owner. Catherine had several children with her enslaver, including Dawley’s father, Mustapha Shaw, who served a soldier in the 33rd Regiment of the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War.

After Union Major General William Tecumseh Sherman completed his famous March to the Sea from Atlanta to Savannah in late December 1864, he issued a special order that set aside 400,000 acres of captured Confederate territory for redistribution to Black families. The plan didn’t last: President Andrew Johnson rescinded it in the fall of 1865, returning the land to its original owners. Shaw was one of the many freedmen who fought back against the reversal, which the newly emancipated “understood as an assault on their hard-won freedom,” wrote historian Allison Dorsey in a 2010 essay. But Shaw’s efforts were unsuccessful, so he returned his birthplace of Harris Neck, buying ten acres from none other than his father and former enslaver.

Turner’s July 31, 1933, recording finds Dawley sharing her family song, which helped her remember her mother, Tawba Shaw, and her paternal grandmother. Today, the aluminum disc is housed at Indiana University’s Archives of Traditional Music alongside 835 other recordings made by Turner between 1932 and 1960.

Until his death in 1972 at age 77, Turner remained dedicated to the study of Gullah and similar languages. His groundbreaking research showed that Gullah, long dismissed by white observers as simply “bad English,” was actually derived from more than 30 African languages.

The dialect’s existence speaks to “the strength of the people brought here as slaves,” Alcione Amos, curator of a past exhibition about Turner at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum, told Smithsonian magazine in 2010. “They couldn’t carry anything personal, but they could carry their language. They thought everything was destroyed in the passage. But you can’t destroy people’s souls.”

_____________

Turner’s work was foundational for subsequent Black language scholars, including Opala, the anthropologist who identified the African counterpart to Dawley’s song. After graduating from college in 1974, Opala joined the Peace Corps, which shipped him off to Sierra Leone, where he worked with rice farmers before shifting focus to archaeology.

“The U.S. ambassador at that time, Michael Samuels, urged me to do an archaeological survey of Bunce Island”—the first of its kind, says Opala. Begun in 1976, the excavations “led to my efforts to find out where the enslaved people shipped from that island were taken.”

Ethnomusicologist Schmidt was teaching at Sierra Leone’s Fourah Bay College when Opala requested her help in studying Turner’s recordings of Gullah stories and songs. The pair spent six years collaborating with Sierra Leonean linguist Koroma and Mende man Edward Benya to reconsider and correct Turner’s original translation. Ultimately, the group settled on this phrasing:

A wa ka, mu mone; kambei ya le’i; lii i lei tambee

A wa ka, mu mone; kambei ya le’i; lii i lei ka

Haa so wolingoh sia kpande wilei

Haa so wolingoh, ndohoh lii, nde kee

Haa so wolingoh sia kuhama ndee yia

Translated into English, the lyrics read:

Everyone come together, let us struggle; the grave is not yet finished; let his heart be perfectly at peace.

Everyone come together, let us struggle; the grave is not yet finished; let his heart be very much at peace.

Sudden death commands everyone’s attention like a firing gun.

Sudden death commands everyone’s attention, oh elders, oh heads of the family.

Sudden death commands everyone’s attention like a distant drumbeat.

The breakthrough came when Koroma recognized a word from the song as a Mende dialect from southern Sierra Leone. In 1990, the researchers traveled around the country’s Pujehun District, playing the song for villagers in hopes of finding someone who recognized the words. Schmidt says she and her colleagues acknowledged that this was a “remote possibility,” but after many weeks, they found a small village, Senehun Ngola, and a woman named Baindu Jabati who astonished them by singing a nearly identical version of the song.

Jabati revealed that the tune—taught to her by her grandmother—was originally a funeral elegy. As Jabati explained in the 1998 documentary The Language You Cry In, her grandmother said that “those who sing this song are my brothers and sisters.” Given the similarities between the two songs, the researchers concluded that Dawley’s ancestors hailed from this specific area of Sierra Leone.

Schmidt and Opala reached out to Dawley’s daughter, by then married and known as Mary Moran, to share their discovery. But the outbreak of the Sierra Leone Civil War in 1991 prevented Moran and Jabati from connecting in person. During the conflict, Jabati was enslaved by rebels, who killed several of her family members and razed her village. By 1997, the war had eased enough for Moran to travel to Senehun Ngola, where her meeting with Jabati was recorded for The Language You Cry In.

The documentary concluded with a message from the village’s blind, 90-year-old chief, Nabi Jah, who encapsulated hundreds of years of trauma by saying, “You can identify a person’s tribe by the language they cry in.”

Since the song contains about 50 words, it’s “almost certainly the longest text in an African language ever preserved by an African American family,” says Opala. “By comparison, [Roots author] Alex Haley was led to his roots in the Gambia by about five or six words in Mandinka.”

In her 1986 book, Radiance From the Waters: Ideals of Feminine Beauty in Mende Art, art historian Sylvia Ardyn Boone wrote that the Mende people remember “a vast storehouse of information” through the use of song. According to Boone, when someone dies, “the ear remains alive.” The Mende repeat the mantra “Ngoli nda ii haa ma,” which translates to “There is no death [within] the ear.”

_____________

In addition to shedding new light on Dawley’s story, Opala joined other scholars in tracing the ancestry of a 10-year-old African girl named Priscilla, kidnapped in 1756 from Sierra Leone, to a 21st-century woman living in South Carolina. Today, Dawley’s family keeps her legacy alive with repeated visits to Sierra Leone and ongoing charitable support. “The 1619 Project” miniseries, based on the New York Times investigation of the same name, shared the story of Dawley’s father, Shaw, and featured interviews with some of her descendants.

Identifying the origins of Dawley’s song “solidifies my identity, because I know where I came from,” says Dawley’s great-nephew, Winston Relaford. “I am no longer another person with a general origin. I now know who I am.” For Relaford and his relatives, the lyrics mean neither “slavery nor the width or depth of the ocean could keep [them] separated” from their Sierra Leonean heritage.

(Originally published by Smithsonian Magazine and edited by Meilan Solly.)

This Black Football Player Was Fatally Injured During a Game. A Century Later, a College Stadium Bears His Name

This Black Football Player Was Fatally Injured During a Game. A Century Later, a College Stadium Bears His Name

Rival athletes trampled Jack Trice during his “first real college game.” He died two days later at age 21

On September 29, 1923, ahead of the football season’s opening kickoff, Jack Trice stepped onto the field at Iowa State College as the school’s first Black athlete. According to the student yearbook, the Iowa State Cyclones easily defeated Simpson College, whose first dropkick “was neatly blocked by Trice, star tackle.”

Nine days later, Trice was dead at age 21. The cause of death: “traumatic peritonitis” from internal injuries sustained during the second football game of the season.

Iowa State’s first Black athlete

It was 1922 when Trice first arrived in Ames, Iowa, with three of his teammates from East Technical High School in Cleveland. They were accompanied by their former coach, Sam Willaman, who’d recently become Iowa State’s new head football coach. Willaman had persuaded the athletes to help form the nucleus of a powerful team in Ames, but since NCAA regulations barred freshmen from competing on varsity squads, they would need to wait a year to take the field for a major game.

Back home, Trice and his teammates had dominated Ohio football circles. In the 1920 season—their junior year—they made it to the national championship game but lost to Everett High School. The next season, East Tech was set to play for the title against Bryan High School in Texas, but the team backed out after learning Trice would not be allowed to compete on account of his race. As a player told the local newspaper, “[Trice] gave us the best he had—we owe it to him.”

In a column for the Waco News-Tribune, Texas sports commentator H.H. “Jinx” Tucker suggested Bryan allow Trice to play, ominously predicting that he would be “carried off the field at Cotton Palace park. More than likely, he would be embalmed.” Tucker knew his audience: It’s possible some readers were among the 10,000 people who participated in the gruesome lynching of farmhand Jesse Washington in nearby Waco in 1916. Many more were complicit in Texas’ institutionalized system of segregation.

At Iowa State, Trice majored in animal husbandry and competed on both the freshman track and football teams. As the son of a farmer, he wanted to use his degree to uplift other Black farmers throughout the Cotton Belt.

Ames was a community with very little diversity. According to a 2010 journal article by historian Dorothy Schwieder, only “20 or so Black students were enrolled at [Iowa State], a college of around 4,500 students.” Most lived in downtown Ames, separated from their classmates by an unofficial policy barring non-white students from living with white students.

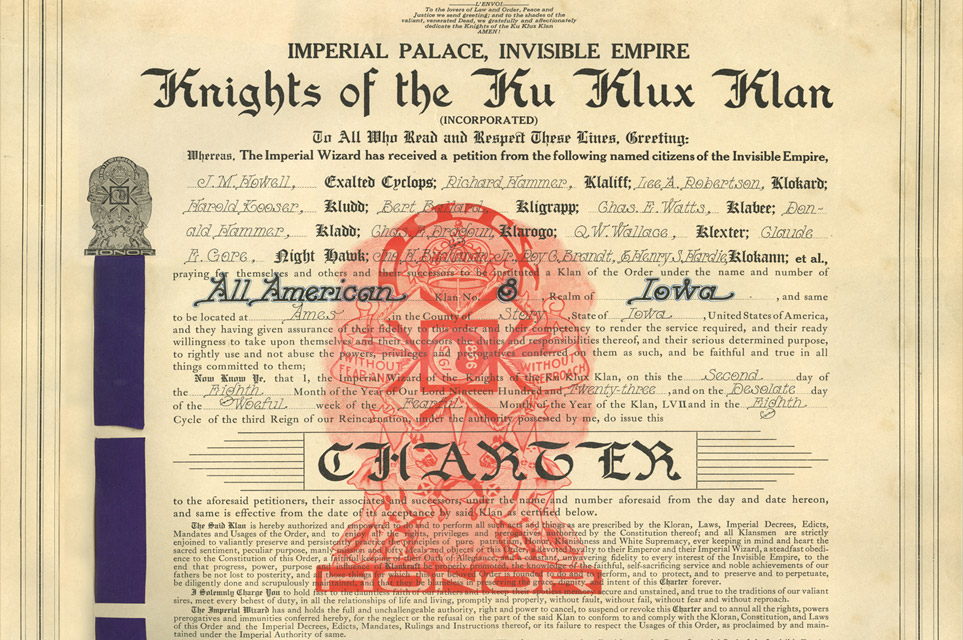

Trice brought his wife, Cora Mae Trice, to Ames in the summer of 1923, around the same time that members of the Ku Klux Klan officially formed a local chapter in the city. It didn’t take long for the Klan to start burning crosses in Ames. Nationally, the Klan was in the middle of a huge expansion, capitalizing on cultural upheaval and white Protestants’ desire to maintain the status quo to fill the ranks of their white supremacist organization.

The 1923 Simpson game marked Trice’s much-anticipated varsity debut. Iowa State fans watched Trice tear around the field, using his speed and power to create havoc. Among them was Cora Mae, attending her first game in Iowa.

A photograph of Trice taken during the Simpson match is the highest-quality snapshot among the few surviving images of him in action on the football field. Startling in its immediacy and sharpness, the image captures a brief moment in between plays. In those days, games moved quickly. Endurance was necessary, because players had to play both offense and defense. As an offensive lineman, Trice opened up holes for the backfield to dart through; as a defensive end, he held down the line of scrimmage.

Iowa State won the Simpson game despite less-than-stellar conditions on the “muddy, slippery field,” as the student yearbook noted. The team was eagerly looking forward to its next game against the University of Minnesota, which was considered the season’s first major match because Simpson was “a much smaller school than [Iowa State] and not regarded as a serious threat,” according to Schwieder.

A fatal injury

Before catching the overnight train to Minneapolis with his team, Trice bid farewell to Cora Mae. It was an experience she never forgot. “He came to tell me goodbye,” she recalled in a 1988 letter. “We kissed and hugged, and he told me that he would come back to me as soon as he could.”

When they took the field in Minneapolis on Saturday, October 6, the Iowa State athletes donned new gold jerseys utilizing the latest design advancements in college football. “Our intention is to reduce the weight and gain speed without sacrificing protection to the individual player,” Willaman told the Iowa State Student. Pads were built into the elbows, and manufacturers started adding friction cloth to the front and sleeves. Athletic catalogs offered several design options, the most popular being two ovals or vertical stripes on the chest.

The jersey redesign spoke to a fundamental shift in college football after World War I. Scarred by the carnage of the Great War, Americans embraced entertainment and pleasure, including college sports. Major universities started building new concrete stadiums. Some were named Memorial Stadium in honor of American soldiers killed during the conflict. The rapid expansion of radio brought thrilling football plays to living rooms and turned athletes into stars.

Waiting for the Cyclones in Minnesota were the Golden Gophers, led by All-American Earl Martineau and Coach William Spaulding. They posed a formidable challenge, but the Iowa State team was ready.

Once the game started, the Gophers targeted Iowa State’s star players, including Trice. He suffered a serious shoulder injury in the first half (later identified as a possible broken collarbone) but insisted he was still able to play. During an offensive play in the third quarter, Trice tried to perform a rolling block, but the Minnesota backfield overwhelmed him, knocking him to the ground and trampling him. Whether the intensity of the team’s response was motivated by racism remains the subject of debate, but Iowa State apparently didn’t think so. After Trice’s death, Willaman scheduled another game with Minnesota for the 1924 season.

After the trampling, team captain Ira Young and lineman Harry Schmidt helped Trice off the field. (Young’s torn, stained football jersey is the only known artifact to survive from the game.) “He was removed from the game immediately, against his wishes, and taken to [the] university hospital,” where a doctor “at once pronounced his condition serious,” the Minneapolis Star reported.

The game concluded with a 20-17 victory for Minnesota. But the Iowa State players had more pressing matters on their minds than the loss. Physicians decided Trice was healthy enough to endure the long overnight train ride back to Ames, where, on Sunday morning, he was whisked away to the campus hospital. As his condition worsened, doctors brought in a stomach specialist from Des Moines, but nothing could be done. Trice’s friends and family could only pray.

The end came on Monday afternoon. As Cora Mae wrote in her 1988 letter, “He looked at me, but never spoke. I remember hearing the Campanile chime 3 o’clock. That was Oct. 8th, 1923, and he was gone.”

Commemorating Jack Trice

On Tuesday, October 9, Iowa State canceled classes, and several thousand people attended Trice’s funeral, which was held on the lawn near the iconic Campanile. Speaking to the crowd from a raised platform behind Trice’s coffin, Iowa State President Raymond Pearson started reading a letter found in the athlete’s personal possessions after his death.

The day before the Minnesota game, the Iowa State team had checked into the Curtis Hotel in downtown Minneapolis. While Trice was allowed to stay at the hotel, he was barred from eating in the dining room with his teammates or being around white guests. Isolated in his room, Trice began writing on a small sheet of hotel stationery:

To whom it may concern:

My thoughts just before the first real college game of my life. The honor of my race, family and self are at stake. Everyone is expecting me to do big things. I will! My whole body and soul are to be thrown recklessly about on the field tomorrow. Every time the ball is snapped, I will be trying to do more than my part.

Trice’s letter was reprinted in newspapers across the country. A few months later, his words were memorialized on a bronze tablet in the Iowa State gymnasium.

Cora Mae dropped out of school and returned to Ohio to mourn. She went back to Iowa State the following year but never graduated. She remarried in 1926 and died in 1993. Trice’s mother, Anna Trice, didn’t arrive in time to see him before he died, but she returned to Ames several times. In a letter to Pearson, Anna wrote, “He was all I had, and I am old and alone. The future is dreary and lonesome.”

Jack Trice Stadium

In the decades after Trice’s death, his story receded from memory, only resurfacing every so often. In 1957, Iowa State student Tom Emmerson learned about Trice and wrote an article on him for a student magazine, but it attracted little response.

It was only in 1973, on the heels of the civil rights movement’s calls for Black equality, that Trice’s achievements garnered more widespread attention. According to a 2008 journal article by Jaime Schultz, Alan Beals, a counselor in Iowa State’s athletic department, happened upon Trice’s memorial plaque—by then “covered in rust, dust and bird droppings”—and decided to co-write a story on him for the student newspaper. English professor Charles Sohn, who had already discussed Trice with Beals, assigned his freshman students to look into Trice’s life. Their efforts helped spark a student movement to name the school’s new football stadium after Trice. But university leaders refused, preferring Cyclone Stadium to honor all athletes.

The fight to name Iowa State’s stadium Jack Trice Stadium continued for a decade. One key figure in the campaign was the irascible Des Moines Register writer Donald Kaul, who continually revisited the issue in his columns.

Kaul needled officials who kept deflecting or delaying with no real resolution. “They mumble low, they mumble high, and soon the question is borne aloft on clouds of mumble,” wrote Kaul in 1975. In a separate column, he claimed to have visited “a witch I know in Georgetown” and asked her to place “a conditional curse … on the team.” He reportedly told her, “If the university officials, a small band of willful men much given to thwarting the popular will, should fail to give Jack Trice the recognition he deserves … the school should not win a game in the stadium.”

In 1984, Iowa State tried to appease everyone by formally naming the stadium Cyclone Stadium and the playing field Jack Trice Field. Kaul lamented the compromise, later writing, “Iowa State has had to be dragged kicking and screaming” to it. The matter seemed settled, but remarkably enough, Trice proponents kept pushing. Finally, in 1997, Iowa State President Martin Jischke formally renamed the arena Jack Trice Stadium.

In recent years, the Iowa State football program has honored Trice with a new logo modeled on his jersey and a patch on players’ uniforms. The logo is emblazoned on the side of the school’s football facility, visible from Jack Trice Stadium.

Last fall, a century after Trice’s arrival in Ames, Iowa State began a yearlong commemoration of him. The school’s slate of events include the unveiling of a new sculpture at Jack Trice Stadium and an inaugural Jack Trice Legacy game against Texas Christian University on October 7. During the game, the team will wear special throwback uniforms inspired by Trice’s story.

“Trice committed himself to being an honorable, stand-up man,” Greg Bailey, head of Iowa State’s special collections and university archives, tells Smithsonian magazine. “[This] was exemplified in his ideals of service.” Today, Jack Trice Stadium is the only Division I Football Bowl Subdivision stadium across the United States to bear the name of a Black man.

(Originally published by Smithsonian Magazine and edited by Meilan Solly.)

Ancient Greeks Built a Road and Primitive Railway to Haul Cargo Overland

Ancient Greeks Built a Road and Primitive Railway to Haul Cargo Overland

Thousands of years before modern railroads appeared, the Diolkos stone road featured a section of grooved tracks and spanned across the Isthmus of Corinth.

Beginning as early as 600 B.C., the ancient Greeks created the Diolkos, an ambitious road partially paved with stone, that spanned across the entire Isthmus of Corinth. The overland route allowed sailors to avoid the perilous circumnavigation of the Peloponnese peninsula. One section of the road featured purposefully grooved tracks—considered among the earliest known railways in recorded history.

The Diolkos was “the first systematic attempt to facilitate the portage of merchandise and warships from the Saronic to the Corinthian Gulf and vice versa,” says Dr. Georgios Spyropoulos, assistant director of the Corinthian Ephorate of Antiquities.

Ancient Corinth: A Bustling Center of Trade

Located on an isthmus west of Athens, ancient Corinth was a powerful, wealthy city that controlled commerce by land and sea. The region was home to the Isthmian Games, held in honor of the sea god Poseidon. Olive oil, wine, textiles, pottery and other forms of exotic trade flowed throughout the region.

South of the Corinth isthmus was Cape Maleas, which tore vessels to pieces and plunged sailors to their deaths. In Homer’s Greek epic Odyssey, the heroic Odysseus tried to sail through these dangerous waters but was blown off path and ended up in the land of lotus-eaters. Rather than braving the treacherous southern route, some ancient travelers used the Diolkos, which bridged the 4-mile distance between Corinth’s primary western and eastern ports.

Centuries later, in A.D. 67, The Roman Emperor Nero attempted to build a canal between Corinth’s ports using thousands of slaves, but the project was soon abandoned.

Construction of the modern (but narrow) Corinth Canal was started in 1882 and completed by 1893.

Discovery of the Diolkos

Starting in the late 1950s, archaeologist Nikolaos Verdelis excavated parts of the Diolkos and dated it to around 600 B.C. during the reign of Periander, the Second Tyrant of the Cypselid dynasty that ruled over ancient Corinth. One legend says Periander built the road instead of a canal because his priests warned “the anger of the two oceans at being mingled would result in the downfall of Corinth.”

After ships approached the coast via the Gulf of Corinth, they “were hauled over a sloping stone-paved jetty, the west end of which was probably underwater, upon wooden rollers, before being hoisted onto the wheeled vehicle,” says Spyropoulos. Many wagons were laden with heavy cargo, likely timber or marble, and pulled by animals.

The Diolkos varied from 15 to 20 feet wide and was paved with poros limestone. Some stone blocks were taken from abandoned monuments and archaic Greek letters were still visible. The Diolkos stretched for about 5 miles because it was built around the landscape to ensure a consistently mild inclination of less than 1.5 percent. No trace remains of the eastern portion and the exact terminus is unknown.

As the Diolkos curved inland, excavations revealed that the worn wheel ruts gave way to a unique railway, carefully and purposefully cut into the stone. “Verdelis [the archaeologist] was right to read these as cut grooves,” says Dr. David Pettegrew, professor of history and archaeology at Messiah University. The grooves measured 5 feet wide and were clearly engineered to accommodate wheels.

The Diolkos was part of a larger road network meant to move people, ships, and cargo. Other rails existed in the ancient world, but they had a singular purpose, such as moving stone out of a quarry to a staging area, and so aren’t considered a true precursor to modern railroads.

Warships Crossing the Isthmus

Most historians now believe ancient warships were not regularly moved overland via the Diolkos, but ancient texts suggest it was used at times in this way.

In the History of the Peloponnesian War, Greek historian Thucydides recounted the first Isthmus crossing in 412 B.C. when Spartans secretly moved their warships across “with all speed” towards Athens, rather than braving the treacherous sea voyage. Other ancient chroniclers, including Polybius, wrote about several more dramatic journeys over the centuries.

One such event occurred in 102 B.C. when Rome dispatched Marcus Antonius, the paternal grandfather of Mark Antony, to attack Cilician pirates. His fleet portaged across the Isthmus and sailed to Pamphylia to his eventual triumph.

Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote about Octavian’s military maneuvers during the War of Actium in 30 B.C. and noted “because it was winter, he carried his ships across the isthmus” and returned “to Asia so quickly” that the feat startled Mark Antony and Cleopatra, for they “learned at one and the same time both of his departure and of his return.”

The Greek government is restoring and protecting some sections of the Diolkos to prevent further wear and erosion. Ongoing excavations may yield further details about the ancient engineering feat and its uses.

(Originally published by History Channel and edited by Amanda Onion.)

5 Extraordinary Ancient Stadiums That Influenced Future Arenas

5 Extraordinary Ancient Stadiums That Influenced Future Arenas

Ancient Greek and Roman stadiums were built to impress—and their designs are seen in many college football stadiums today.

Ancient Greeks and Romans placed immense importance on the pageantry and competition of sport, transforming modest playing fields into a connected network of stadiums designed to honor the gods and affirm their power. The stadiums’ extraordinary designs have inspired new structures for thousands of years.

From the 1900s to 1920s, college football saw a massive increase in popularity, and ambitious architects followed Greek and Roman design in the construction of monumental stadiums that sprang up on college campuses across the country.

Here are five ancient stadiums and some of their enduring influences.

Amphitheater of Pompeii

Pompeii was a town replete with erotic art and gladiator matches that drew thousands of fans. When Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79, volcanic ash preserved the oldest Roman stone amphitheater. The small oval arena interior was lush with thematic frescos “depicting wild beast hunts (such as a bear fighting a bull) and combat,” as Joanne Berry writes in The Complete Pompeii.

The exterior featured several peculiar trapezoid staircases, each supported by six arches, that led to the apex. According to Yale art historian Diana E. E. Kleiner, this staircase design was “never to be repeated” and there is “no other one like it in the history of Roman architecture.”

The Yale Bowl, opened in 1914, copied Pompeii’s amphitheater by excavating a giant earthen oval and building seats into the newly formed hills. According to Yale Alumni Magazine, engineers designed the field so “‘the minor axis points to the sun at 3 p.m. on November 15. Thus no football player would ever have to look into the sun when Yale plays its big games against Princeton and Harvard.'”

Roman Colosseum

Located in the pulsating center of ancient Rome, the Colosseum was built on top of the former Emperor Nero’s ruined palace and opened in A.D. 80 with a series of anticipated games. It was inspired by the earlier and slightly smaller Amphitheater of Capua where the enslaved Spartacus started a revolt, triggering the Third Servile War.

The Colosseum’s brilliant design efficiently managed crowd flow with dozens of vomitoria, or openings, throughout the arena. Designated sections allowed elites to enter, exit and mingle in their own personal corridors. Along the ground level were sections for shops and stalls. The stadium even featured pipes, sometimes hidden in statues, that misted spectators with a perfume often made from saffron steeped in wine.

Before Ohio State opened its new horseshoe stadium in 1922, architect Howard Dwight Smith wrote about the Roman influences in his design. The massive upper deck that swept around the entire stadium exterior was borrowed directly from the Colosseum’s own top story with “its small, square windows and its engaged pilasters.” Additionally, Smith echoed the Pantheon with his famous coffered semi-dome entrance on the north end. The Ohio stadium does not, however, feature discrete perfumed misting.

Stadium of Delphi

The mystical site of Delphi, situated amidst a gorgeous mountain range, was the omphalos, or hub, of ancient Greek culture and centered around the cult of Apollo and a mysterious oracle. The Stadium of Delphi held footraces as part of the Pythian Games and, unlike the older and more prestigious Olympics, women were allowed to compete in some events.

Delphi’s “stone stadium is far superior to Olympia,” says Jeffrey Segrave, professor of exercise science at Skidmore College. “The seating at Delphi is quite remarkable—12 rows of seats, special seats for the dignitaries, all divided by stairways.” Compared to Olympia’s simple earth banks, “Delphi looks like a real athletic venue.”

When Stanford University planned its new stadium in 1921, they kept costs reasonable by creating an earthen bowl, but included a unique feature. One section of the bowl was broken up by an excavated gulley to accommodate a long track straightaway leading away from the bowl. Stanford boosters pointed out the resemblance to Delphi’s own design that plowed through the hillside.

Circus Maximus

The chariot races of Circus Maximus, the largest circus of all, held over 200,000 spectators in suspense as charioteers in team colors raced laps around a 2,000 foot-long sand track. All circuses consisted of the oblong racetrack with a long stone wall divider called a spina running down the center. The spina was lined with various monuments and statues, including an Egyptian obelisk—a tall, four-sided, monument capped with a pyramid. The towering obelisk illustrated Rome’s power and wide reach. Rome’s various circuses also hosted athletic events, gladiator matches and animal hunts.

In 1903, Harvard’s new concrete stadium opened as the largest collegiate stadium of its time. This was during an era when other schools had rickety wooden bleachers lining the field. The design resembled an ancient Roman circus and, thanks to Harvard’s influence on college football, others took notice. During the 1920s stadium boom, dozens of schools followed in Harvard’s footsteps.

As Michael Oriard writes in King Football, boosters and sportswriters imbued college football with “overblown classical allusion: football players as gladiators, the stadium as a Circus Maximus, contending teams as Greek and Persian legions.”

Panathenaic Stadium

Panathenaic Stadium was originally opened by orator Lykourgos in 330 B.C. Then around A.D. 140, Herodes Atticus rebuilt it using white marble from the nearby Mount Penteli. The stadium was constructed in a natural ravine between two hills, and remains the only stadium built entirely out of marble. Like other ancient Greek stadiums, it centered around the stadion (also called the stade), a footrace that is the first Olympic event noted in written records.

The stadion was 600 Greek feet, but regional variations meant the actual track length slightly varied from stadium to stadium. One common length was approximately 185 meters and scholars have also cited 176 meters, which was a close match to the track straightaway at the Panathenaic and Delphi stadiums.

When Harvard built their stadium, the footprint measured approximately 185 meters while the stands ended after about 176 meters—an intentional match to the Panathenaic Stadium—as a way to connect college football to the great ancient stadiums of lore.

(Originally published by History Channel and edited by Amanda Onion.)

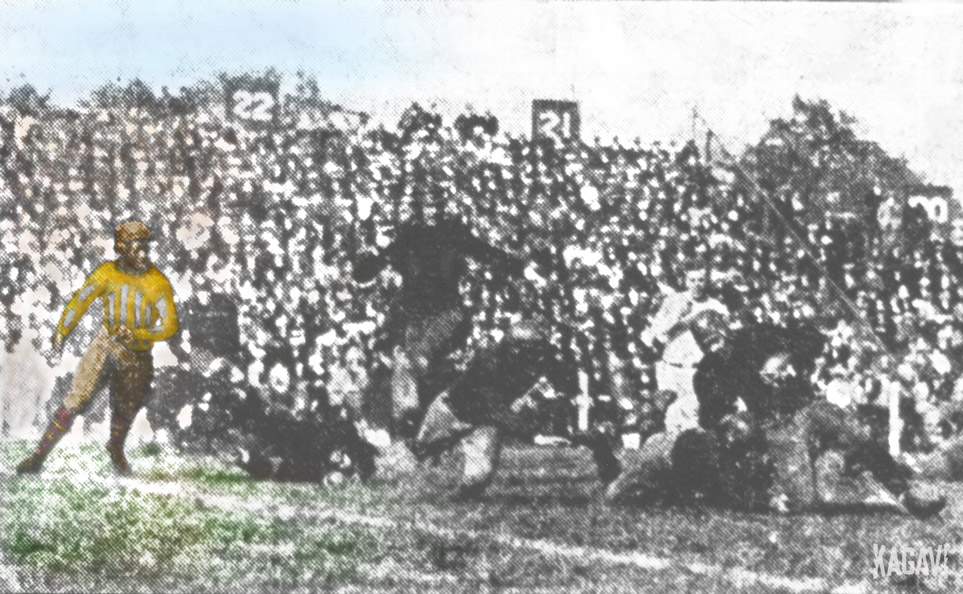

Adding color to Jack Trice’s fatal game

Some years ago, I came across the only known photo of Jack Trice playing against Minnesota and it was a small, blurry, dark image. When I published that story in 2018, I hoped I would eventually be able to find something else from that game, but so far I’ve come up empty–although there are still some dark corners that I’m digging through. In the absence of an original photo, there was only so much I could do to bring Jack to life in that game.

But why stop there?

Since I have Ira Young’s 1923 Iowa State jersey and extensive knowledge of that doomed fall season, I decided to try adding color to the Minnesota game, despite the immense challenges that came with working on a small copy of a copy of a copy of a copy. (Not an exaggeration.) Across large swaths of the image, I was presented with a binary choice of black or white with absolutely nothing else. Vacillating between extremes, I teased out the tiniest specks of tonal differences and used those as a starting point.

There was also his equipment. On the left side of Jack’s head, there’s a small line that likely represented the collar of his shoulder pads peeking out, thus giving me a hint of where to apply some colors. His helmet was also the same one from the Simpson game photo the previous week, so that helped. I ended up layering 15 different shades of color on his uniform and many other tricks and barely had enough to pull it all together.

Other photos, especially the ones from spring 1923, are in a much higher quality and would be vastly easier to colorize, but don’t have the emotional impact of showing Jack minutes away from his fatal injury. This is also perhaps the final image of his life that still exists. The end result isn’t perfect, but every little step brings me closer to 1923.

Here is Jack Trice playing on Northrop Field in color.

Jack Trice and the Ku Klux Klan

I am haunted by Jack Trice’s life and cannot stop thinking about his last days. Over the years, I’ve often mused on the role of the Ku Klux Klan in that era and searched for an answer that simply doesn’t exist. Many popular stories only mention the presence of the Klan in Minnesota when the Iowa State team arrived for their game. The reality is much messier and adds crucial context to Jack’s tragic letter.

We should first consider an obscure tale from Jack’s senior year in high school, which I initially found in 2014. At the time, I was researching why East Tech’s football team didn’t play in another championship game in 1921, but set it aside because I felt there was a bigger story to tell. It took several years for me to piece together the full story and the shocking truth served as an ominous harbinger of events to come.

Two years later, the Ku Klux Klan sealed their presence in Ames. This is the untold story.

_____________

In high school at East Tech, his wide eyes drinking up the city around him, Jack saw very quickly Cleveland wasn’t the small country village he grew up in. Custom dictated withdrawal here. The Great War whisked up East Tech students and they learned what burning flesh smelled like on the Western Front. Back home, the Spanish Flu took ragged bites out of America. Bodies piled up.

East Tech made sure no one forgot the sacrifice of those who never returned.

In 1920, Jack was one of several junior players who helped East Tech polish off an undefeated regular season that culminated with a bid to the prep national championship game in Washington–a game I previously wrote about. The boys rode the rails for a week and bonded on the trip. They played cards, sang, and giggled their way through spectacular western landscapes.

During Jack’s senior year, East Tech didn’t miss a beat, rolling to another undefeated season. The papers praised his play far and wide. He had come a long way and was one of the best players in the country, a colossal talent. In addition to his suffocating play on the line, he played some at fullback and shared punting duties. He could do it all and nothing could stop him.

Opposing fans took umbrage. They lashed out in anger and hurled insults. After one emotionally charged game that ended in victory, Jack was called a “monkey.” He always had to live with the implicit threat of bloodshed lurking in the shadows. When another high school was clobbered by East Tech, they offered an interesting cartoon recap of the game. Note the mysterious figure in the background.

The postseason beckoned. This time, East Tech would bring the crown home. Schools across the country clamored for a shot. Anticipation teemed.

Negotiations started with a New England school. One school in Minnesota wanted a game on Christmas Day. All potential games fell through, but in mid-December, East Tech agreed to meet Bryan High in Texas for the national championship. Texas was Klan country and the game would be held about 80 miles southeast of Waco, where the infamous torture and lynching of Jesse Washington occurred in 1916.

It was not to be.

When it became understood that Jack, the dread black phantom, presented a problem, his white teammates rallied around him and unanimously voted to give up the trip and their last shot at the national championship. One teammate said, “He gave us the best he had–we owe it to him.”

The Texas papers didn’t handle it well, fuming about the “nigger” who ruined the big game. One celebrated writer invited his readers to share in delightful imagery. Why not have Jack play in the big game before the crowd of thousands? After all, they would make sure he was carried off dead.

It would be nearly two years before Jack played in a big game again–the one that killed him.

_____________

When Jack arrived in Ames, the Klan was already around him. Local papers speculated on how many people would join the organization. One nearby town reported Klan posters were “found in the police office, altho no one was able to explain how.” In communities across Iowa, Klan envoys brought gifts to homes, hoping to win favor.

A couple of years ago, I returned to Ames and met with Alex Fejfar, the Exhibits Manager of the Ames History Museum. The museum is a small gem directly across the street from the Masonic Temple where Jack had his last words with his wife Cora Mae before the Minnesota game.

With Alex as my guide, we rooted through the Masonic Temple basement, peering through the dust of decades, looking for any elusive sign. On the top floor, we retraced steps of long ago and breathed in the memories. In one remote staircase, we were trapped by a locked door closing behind us. It seemed, just perhaps, the ghost of Jack Trice was guiding us.

My list of research questions was immense and we had so little time. Back at the museum, Alex dug through the archives and presented a chilling example of hate so close to home. Thanks to the “Private Collection of Jerry Litzel, Courtesy of Ames History Museum,” we are able to present it here.

In August 1923, awash with patriotic faith in their country and flag, thirteen Ames men stepped forward to enshrine their names on the Ames charter of the “Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.” These men knew they were destined to be “All American” leaders of the Klan “Reincarnation.” Some time later, the Imperial Wizard, Hiram Evans, signed it. The ceremony was complete.

It didn’t take long for the crosses to start burning.

Less than a month later, the Nevada Journal reported a fiery cross was burned on the edge of town as the Ames Klan attempted to intimidate an accused bootlegger. Their presence was impossible to deny any longer. Membership swelled. More crosses were burned. Prominent Ames citizens took pride in their leadership role, including those who walked the Iowa State campus. Unbeknownst to some students they were taught by the Klan, including a very small and real possibility that Jack was among them (which I’m still researching).

Black students at Iowa State were barred from living near campus, so they usually ended up in downtown Ames near the Masonic Temple. Some worked at the Sheldon-Munn hotel. Unfortunately for them, Klan meetings were often held downtown. Members of the hooded order prowled near where Jack and Cora Mae held each other on lonely nights.

Something had to be done.

_____________

Before Jack was a blank piece of Curtis Hotel stationary on the small desk. He was going to be the only Black player on the field against Minnesota. Hundreds of years of anguish and pain flowed from his pen. He was surrounded by hate and carried the burden of all before him. Those who were lynched without a thought. The bottomless eyes of white hoods. Flickering flames reaching high. The game was tomorrow and it was already too late.

“The honor of my race, family, and self are at stake.”

New Jack Trice photo discovered

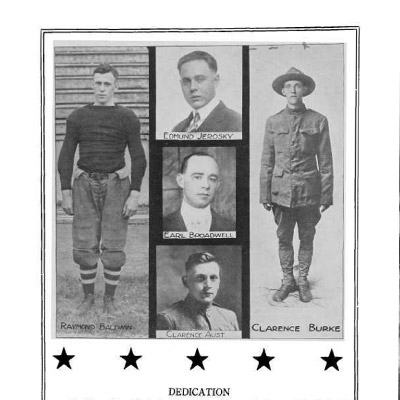

When Jack Trice was in high school at East Tech in Cleveland, all eyes were drawn to him on the football field. His presence was controversial and political. It was rare for Jack to see another Black athlete to commiserate with. In tribute of his sacrifice, I’m pleased to unveil a new photo of Jack Trice playing for East Tech in a game almost 100 years ago.

This discovery was many years in the making.

I was able to use my expertise to descend into a particular, yet obscure, spot of Cleveland history to experience life during the early 1920s. Hunch after hunch had to be followed along an unknown path until one day came the metaphorical clink of my shovel. This photo was not labeled or dated, but I knew immediately. There was the lanky frame of Jack on the right, opening up a hole for Johnny Behm to plunge through. Johnny was the captain of East Tech and went on to become the captain of Iowa State, finishing his career as a honorable mention All-American quarterback.

The photo is not an original copy, but a printed version and white marks are visible on some of the players–which was a common practice for reprinting in newspapers. Johnny is not wearing an helmet again, just like the other photo I discovered of Jack and Johnny in the prep national championship game in Washington, seen in Jack Trice and the Nazi Olympiad.

Once again, let us pay homage to the hero of Iowa State formed in the crucible of East Tech.